The Race to Diffuse AI

How China and the U.S. stack up in AI development and deployment

In November 2024, the bipartisan U.S.-China Economic and Security Review Commission recommended that Congress establish a new “Manhattan Project” to develop Artificial General Intelligence (AGI). In May, Vice President J.D. Vance framed the AI competition between the U.S. and China as an “arms race.” Both statements compare AI capabilities to nuclear weapons, but the two technologies are not wholly analogous. Unlike nuclear weapons, which currently have no use case outside of the military, AI will touch all aspects of life: economic, military, and personal. The “arms” of the AI race, dominated by private companies rather than government labs, are not merely AI-enabled military capabilities but also products that create new efficiencies, cement economic advantage, and harbor global influence. While AI models underpin AI products, the country that leads in AI will be the one who operationalizes it across the economy and military.

Though the U.S. has long led the world in AI research, before ChatGPT’s release, some prominent experts believed China would pull ahead. One of the most influential of these experts was Kai-Fu Lee, whose 2018 book AI Superpowers asserted that China’s ability to commercialize the latest advances in AI, often by copying its American counterparts, would help it accrue greater advantages from AI. Then the breakthrough of ChatGPT quelled some of these fears within the U.S., even while China’s companies rushed to release their own equivalents. For the past few years, observers have judged the AI race through the lens of model performance metrics, an outlook that shaped the Biden Administration’s approach to AI policy – particularly export controls focused on advanced chips and aimed at slowing China’s ability to develop advanced AI models.

But despite U.S.-imposed hurdles like export controls, China found creative ways to rapidly close the gap in model performance. China’s ability to “fast follow” the best U.S. models has called into question what it actually takes to win the AI race. The result is a popularization of the diffusion hypothesis – the belief that adopting AI matters more than being first to develop frontier model capabilities – encapsulated by Jeff Ding’s 2024 book Technology and the Rise of Great Powers. This time, some of its most vocal proponents are U.S. officials. Simply having the best models, these officials now believe, is not sufficient. Undersecretary of Defense Colin Kahl wrote in Foreign Affairs this month that we are in the midst of three AI races: frontier capability, diffusion, and safety. Former AI leads at the Pentagon, Radha Plumb and Michael Horowitz, wrote in the same magazine that “Winning [the AI race] means Deploying, not just developing, the best technology.” And Adm. Samuel Paparo, Commander of INDOPACOM,1 said in May that the military competition in AI depends on who “employs the better models, faster, more extensively, across the force.” In China, Zhang Yaqin, a former executive at AI giant Baidu, explained it succinctly: “American firms focus on the model, but Chinese players emphasise practically applying AI.”

If adoption matters most, the U.S.’s advantage in the AI race – commercially or militarily – is even less certain than its lead in model development. In fact, some data suggests the U.S. is behind. According to an IBM study, 50% of Chinese companies have used AI versus just a third of American ones. 72 local governments in China started using DeepSeek’s R1 large language model (LLM) within weeks of its release, while operators in the US military still struggle to access LLMs on government networks. These disparities reflect common beliefs that Chinese society is more accustomed to adopting AI and automation and that the U.S. government struggles to move new technology beyond research and development into actual production.

Frontier model performance is widely scrutinized; quantifying AI adoption is much more difficult. The high-level statistics above suggest China may hold a lead in AI diffusion, but these statistics are far from conclusive.

The race to diffuse AI is also in its early days. To understand how the race might unfold, we can turn to the structure and progress of China’s AI industry and its current efforts at diffusing AI. In this post, we explore 1) the Chinese AI ecosystem, 2) China’s efforts to diffuse AI, 3) the challenges China faces in AI diffusion, and 4) recommendations for how the U.S. can accelerate its diffusion efforts to outpace China.

China’s ecosystem emphasizes top-down mobilization and open-source, cheap, highly permissive models. These qualities can accelerate diffusion with cheaper models, but the ecosystem faces challenges accessing high quality data and the best available chips, suffers from regulatory censorship, and is limited in its ability to sell into international markets. The U.S. leads at the frontier but lacks analogous top down efforts to embed AI into every facet of the government and economy.

Our recommendations consist of several tactical steps the U.S. government can take to improve its positioning in diffusing AI. First, encouraging open data sharing in the AI ecosystem will bring about the best AI products, which run on high fidelity data. Second, while Chinese models pose security risks, the U.S. government should be cautious about outright banning cheaper, highly performant Chinese models, which may undermine efforts to get enterprises to adopt AI. Third, the government needs to clear more hurdles for adopting AI itself, including by securing access to sufficient compute and licenses to run AI models and applications. Finally, investing in broader AI literacy, including by attracting significantly more skilled labor to the U.S., will help enterprises embed AI into key business workflows.

Broadly, as yet, there is no single metric or rigorous methodology for measuring AI diffusion. The U.S. government should develop such a methodology if it wants to execute a successful strategy for getting ahead.

State of the Chinese AI Ecosystem2

Both the U.S. and China will adopt AI within the constraints of their respective industry and policy environments. China’s environment is unique, affording some advantages and some disadvantages for diffusing AI into Chinese society.

Big Tech Companies

Similar to the U.S., Chinese “big tech” companies play a central role in the Chinese AI ecosystem, both developing AI models and diffusing AI throughout Chinese society. Developing Generative AI (GenAI) models is extremely capital intensive, and achieving widespread diffusion requires strong distribution channels. Unsurprisingly, big tech companies with large user bases and deep pockets play a pivotal role in the Chinese AI ecosystem.

China’s major big tech AI players include Baidu, Alibaba, Tencent, ByteDance, and Huawei. Baidu and Alibaba have both developed well-regarded frontier AI models – ERNIE and Qwen, respectively. Alibaba plans to invest 380 RMB (~$53B) into AI research and infrastructure (more than any other Chinese company) and has contributed significantly to open source AI research in particular with its highly performant Qwen model series. Huawei is China’s leading developer of AI chips, which, although less performant than Nvidia’s cutting edge GPUs, are likely the best option for future Chinese models given export controls and could eventually catch up to the cutting edge with significant Chinese government investment.

As of November 2024, ByteDance developed China’s most popular AI chatbot, based on its Doubao models, which had over 100 million monthly active users and cost 99.8% less than OpenAI’s similar model GPT-4 due to ByteDance’s aggressive price cuts. ByteDance has an edge in the overall AI race due to its access to large troves of user-generated content (UGC) from TikTok / Douyin that it can use to train AI models. ByteDance has already published several AI models capable of generating realistic videos of humans, which were likely trained on UGC.

Tencent and Huawei have both invested heavily in their AI research teams, contributing papers to top academic AI conferences like NeurIPS. Huawei was the 6th largest contributor to NeurIPS from 2021 to 2024, while Tencent was the 7th (Chinese universities Tsinghua University and Peking University, which have deep ties to the AI industry, are the 1st and 2nd largest contributors to NeurIPS). Tencent, Huawei, and Alibaba all run large cloud data centers capable of training and running AI models. Further, Baidu, Tencent, Alibaba, and Huawei offer AI studio platforms on their clouds designed to simplify enterprise adoption of GenAI via model-as-a-service, providing developers with access to closed and open source AI models, Retrieval Augmented Generation (RAG), model training and finetuning for specific application domains, and agentic workflows.3 These offerings mirror AI studio offerings provided by American hyperscalers like Google’s AI Studio, Azure AI Foundry, and AWS Bedrock.

Centralized enterprise platforms could accelerate AI diffusion in both China and the U.S. For example, the hundreds of millions of customers who already use Microsoft’s 365 product suite are able to access Microsoft’s new features in Copilot, its GenAI product offering. Similarly, Alibaba’s DingTalk, an all-in-one platform for communication, productivity, HR, and business automation, offers its own AI assistant. Of course, as we know from our own friends at large companies, just because people are able to access Microsoft’s AI products, does not mean they use those features or find them useful.

China’s consumer tech ecosystem is more centralized than the American consumer market. The Chinese consumer technology market is dominated by WeChat (by Tencent), the “everything platform” that integrates messaging, social networking, payments, e-commerce, government services, and more into a single app. With such disparate data and services offered, Tencent might successfully train powerful and personalized models that become general purpose personal assistants, accelerating diffusion.

Startups

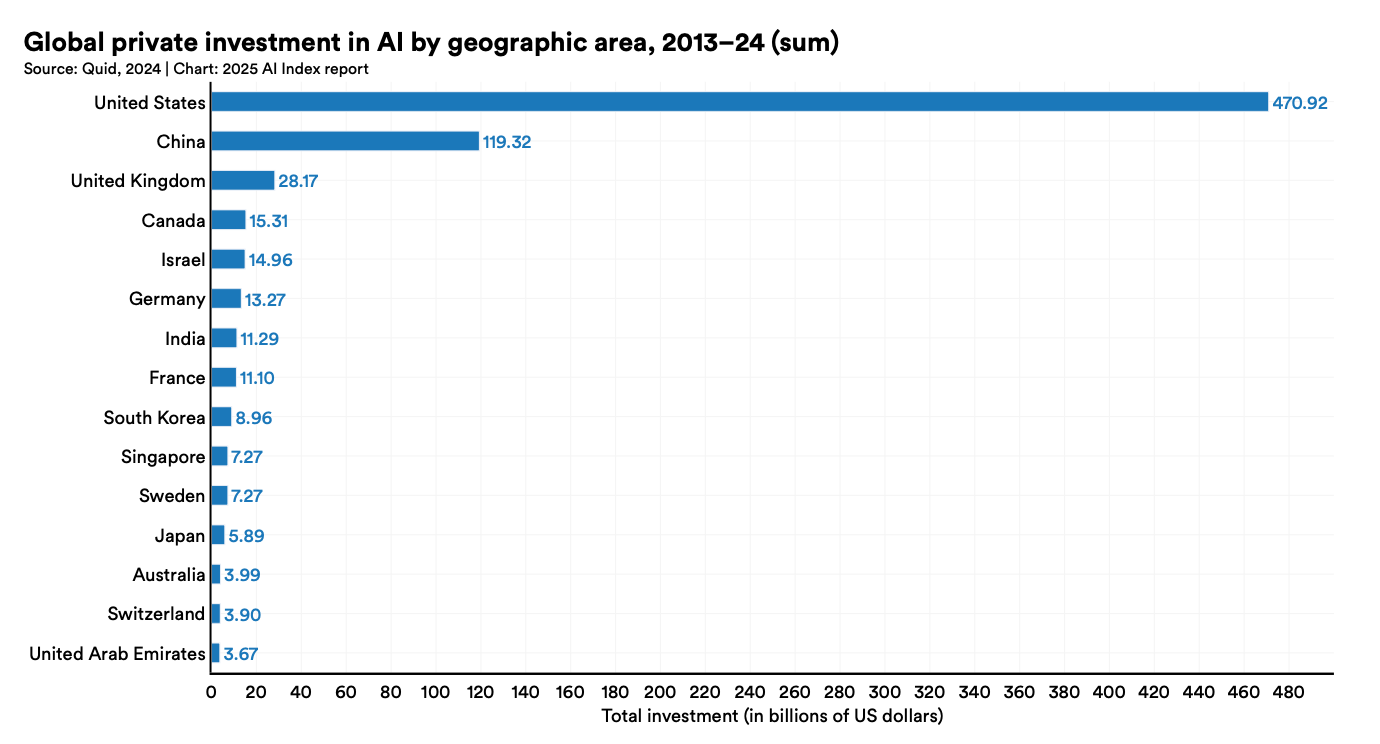

Between 2013 and 2024, Chinese firms invested $119B into Chinese AI – the second most of any country in the world after the $470.92B raised by American AI startups. Spurred by this large volume of investments, a number of new cutting-edge AI startups have emerged, including a group nicknamed China’s “AI Tigers” (also sometimes called “new AI Dragons”). The AI Tigers are six private Chinese AI startups, each valued at over $1B, building large generative AI models: Zhipu AI, Baichuan Intelligence, MiniMax, Moonshot AI, StepFun, and 01.AI. Several of the founders of these companies previously worked at American tech companies – for instance, the founder of StepFun was previously an executive at Microsoft, while Kai-Fu Lee, the founder of 01.AI and author of the aforementioned AI Superpowers, previously worked at Apple, Google, and Microsoft. Many of these startups also have ties to the prestigious Tsinghua University: Zhipu directly spun out of a Tsinghua research lab, and Tsinghua faculty and alumni founded Baichuan AI, Moonshot AI, and MiniMax.

Other notable Chinese AI startups include DeepSeek, which spun out of a Chinese hedge fund that has not raised outside capital, and Manus AI, a Chinese OpenAI competitor which recently raised $75M from American VC firm Benchmark Capital at a $500M valuation. DeepSeek is notable for its release of R1, a highly performant and cost-effective reasoning model. Manus, meanwhile, was able to attract American investors (Benchmark) and stands out for its emphasis on agents rather than basic chatbots. Several other American VC firms criticized Benchmark for its decision to invest in a Chinese company focused on developing AGI, and the company subsequently shut down its office in China.

This new generation of GenAI-focused “AI Tigers” contrasts with China’s previous generation of unicorn AI startups, known as the “old AI Dragons.” The old AI Dragons include SenseTime, Megvii, CloudWalk, and Yitu. These companies primarily specialize in computer vision, focused on tasks like surveillance and facial recognition (China has one of the largest networks of security cameras in the world – around 700 million – many of which are equipped with facial recognition software, to monitor its population). The AI Dragons thrived on Chinese government contracts, including some specifically focused on monitoring ethnic minorities, and faced U.S. sanctions in 2019 and 2020, which slowed their global expansion.

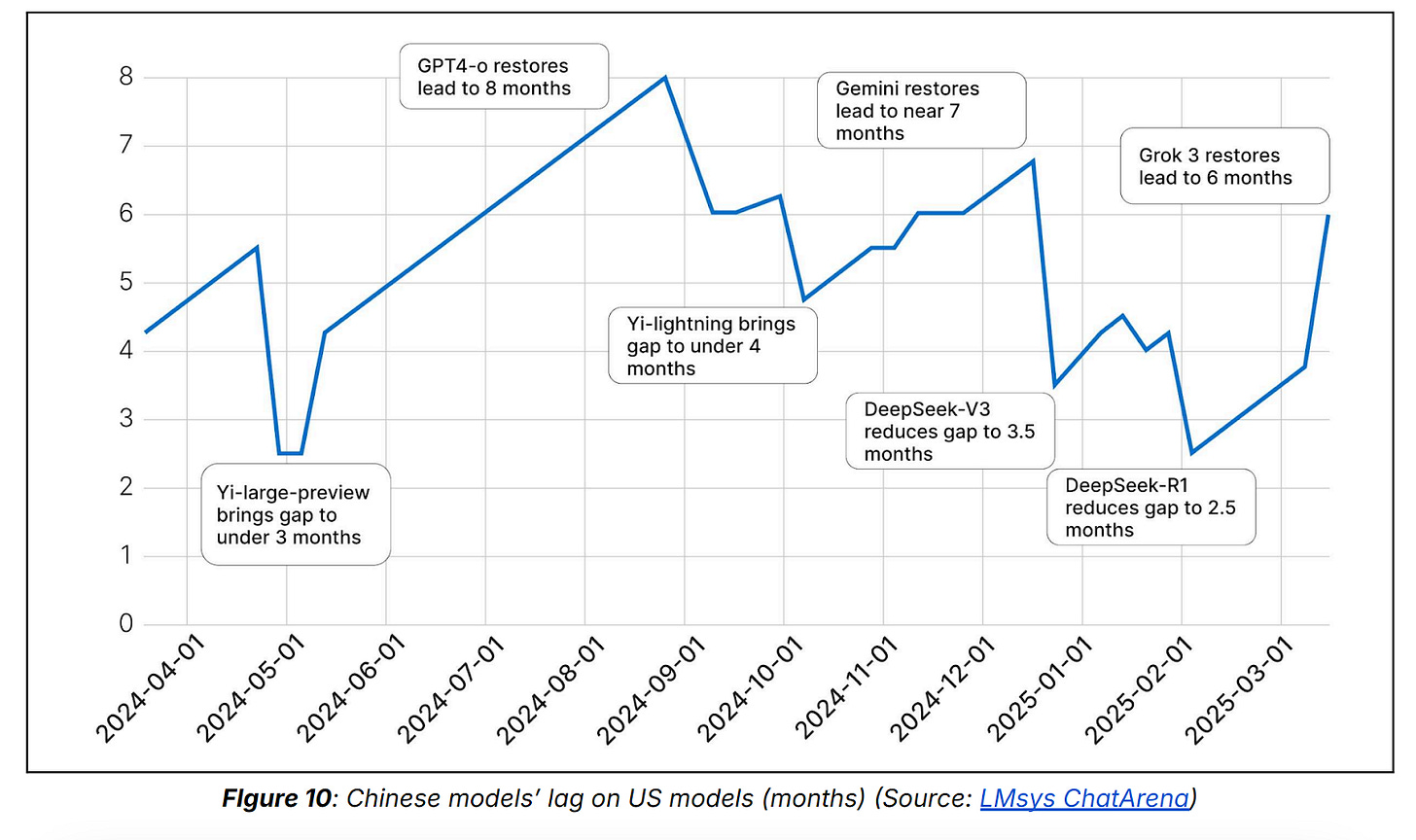

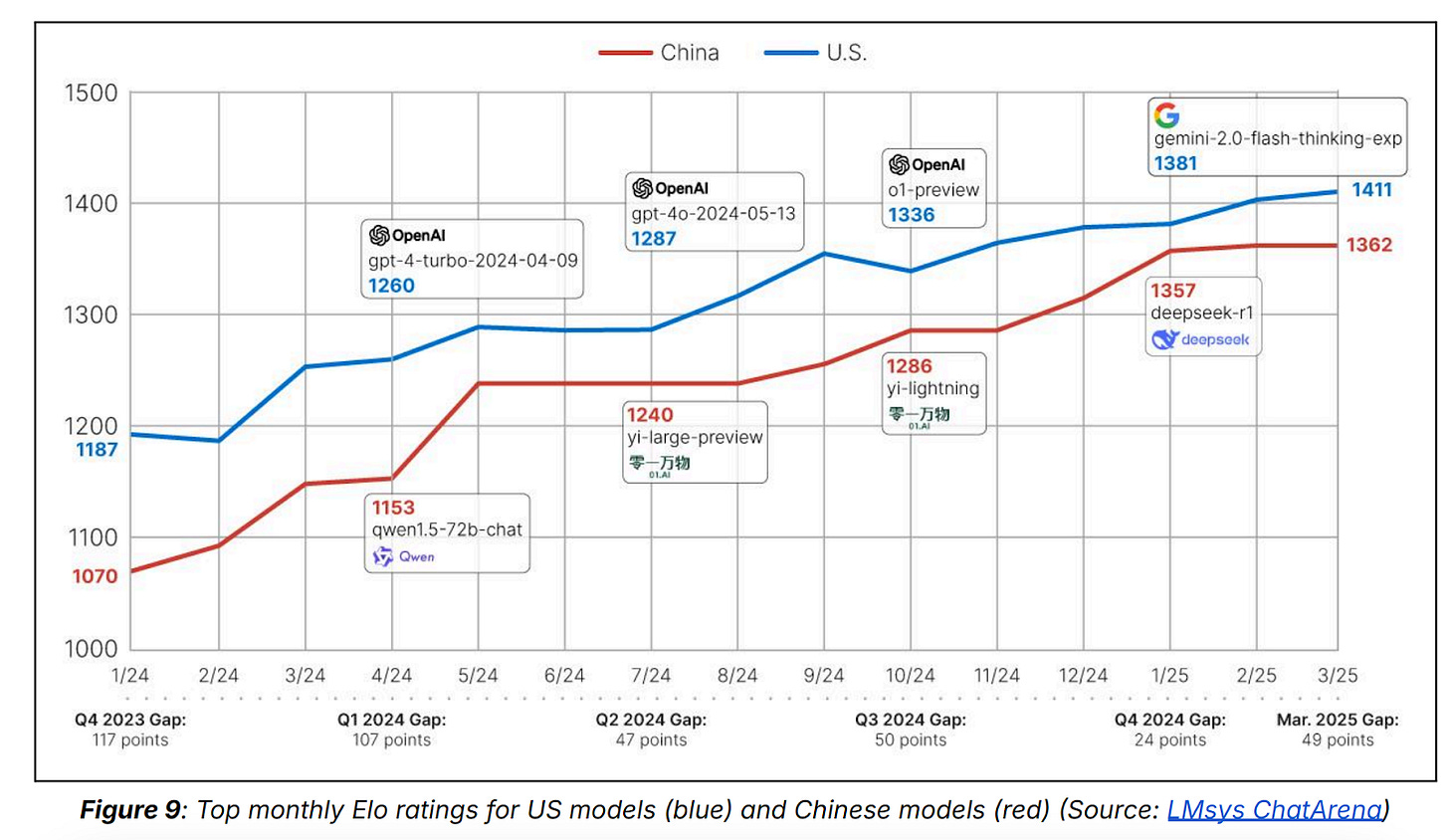

AI Models

In 2024, experts estimated that Chinese AI researchers were about 6-12 months behind U.S. AI researchers. However, experts now believe the gap has narrowed significantly over the past year due to model releases from DeepSeek (R1 and V2), Alibaba (Qwen), 01.AI (Yi), and Moonshot AI (Kimi). Now, researchers say Chinese AI researchers are just 3-6 months behind US researchers.

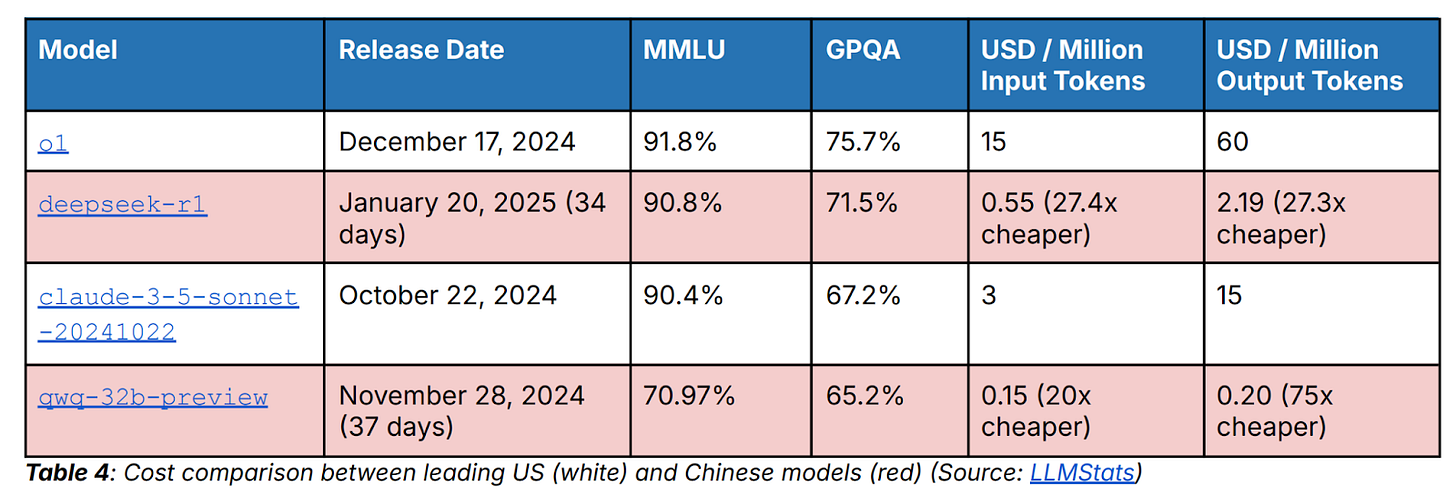

In addition to achieving similar performance, Chinese models tend to be much cheaper than U.S. models. The competitiveness of the Chinese AI industry has led to major price wars between model providers offering ever cheaper models. In May 2024, ByteDance released a model costing ~99% less than OpenAI’s cutting-edge models. The same month, Alibaba followed suit, cutting the price of several Qwen models by 97% to compete with ByteDance. Then, in December 2024, Alibaba cut the price of another model (Qwen-VL) by 85%, and in April 2025, Baidu slashed the price of its Ernie 4.5 Turbo model by 80%.

The AI price war in China is likely worse than in the U.S. because the U.S. GenAI market is dominated by a small number of cutting-edge companies (OpenAI, Anthropic, and Google) that release differentiated frontier models with increasingly better performance. In contrast, Chinese companies tend to release lagging-edge products that are not differentiated from American frontier models or other Chinese models, making it necessary to compete on price. Additionally, Chinese AI researchers are incentivized to develop cheap, efficient models due to U.S. export control-imposed hardware constraints. For example, DeepSeek’s team had to optimize model training and inference to make the most of lower-end hardware, which led to the development of an extremely low-cost model (DeepSeek’s R1 model is about 50% cheaper than OpenAI’s o3-mini, which has similar performance). This extreme focus on low price positions China well to ultimately diffuse AI, as access to cheap models lowers the barrier to entry for adopting AI.

Open Source Advantage

One of the most significant characteristics of the Chinese AI ecosystem relative to the U.S. is its advantage in open source models. This advantage was first apparent with the January release of DeepSeek R1 and has only become more pronounced since. Just last week, Moonshot AI, one of the “new AI Dragons,” released an open source model called Kimi K2, now the best open source model on the market. In contrast, Meta delayed the release of its largest Llama 4 model because it would not be sufficiently state-of-the-art. Meta’s licensing does not allow for commercial use of its models, either, making them far less useful for diffusion across industries than Chinese open source models.

The widening capability gap in open source AI might be the biggest threat to the U.S. in the race for AI diffusion. Open source models offer several diffusion advantages over closed models. First, they can be deployed locally, mitigating data sensitivity concerns. Second, they’re cheaper, because users only need to pay for compute, rather than a usage fee charged by the company. Third, full access to model weights allows technically sophisticated users to engineer the models themselves for their specific, practical use cases.

Chinese AI Adoption

In the U.S., the frontier LLM companies have few forebears in the AI industry. Their emergence has brought forth a new era in the tech industry. Google CEO Sundar Pichai described AI as “more profound than electricity or fire.” For China, the distinction between “old AI Dragons” and “new AI Tigers” suggests a different history. Indeed, this is not China’s, and particularly not the Chinese government’s, first foray into adopting AI.

Historically, American AI researchers have done little work with the U.S. government4 (although, over the last year, the American AI industry has increased its focus on doing so, with new initiatives announced by companies like OpenAI, Anthropic, Meta, and Scale AI). In contrast, Chinese AI companies have long worked closely with the Chinese government, supporting broader AI diffusion throughout Chinese society. AI firms iFlytek and SenseTime, two of the “old AI Dragons,” for example, played significant roles in advancing the Chinese government's surveillance capabilities beginning in the 2010s. Chinese law enforcement leveraged iFlytek’s voice recognition technology to monitor phone calls and public conversations, targeting ethnic minority populations like the Uyghurs. SenseTime provided software for identifying and tracking individuals across large-scale video surveillance networks. The success of the Chinese government’s adoption of computer vision and voice recognition AI helped SenseTime become the largest AI company in the world in 2018. It also landed both companies on the Department of Commerce’s entity list in 2019.

The success of these “old AI Dragons” showcases China’s comfort with deploying AI in production. The integration of computer vision and voice recognition in those years also offers a clue about how the Chinese government thinks about adopting AI today: in addition to strengthening its military and economy, the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) has the added burden of worrying about how AI could undermine its authority, and it aims to use technology instead to strengthen it. China’s ongoing significant spend on internal security, larger than its defense budget, offers an ongoing government stimulus to AI development in China.

The Chinese government has been experimenting with using AI for more than a decade to monitor and control its population and automate various industries. This experience may serve the PRC well as the Chinese government and its people race to diffuse AI.

By the Numbers

How does one actually measure what country is leading in AI diffusion? Are there any metrics that provide a clear picture? Microsoft CEO Satya Nadella recently said that the “real benchmark” signaling AGI is 10% global GDP growth. If AI is truly general-purpose, perhaps only a country’s rapid economic growth can encapsulate its usage of AI.

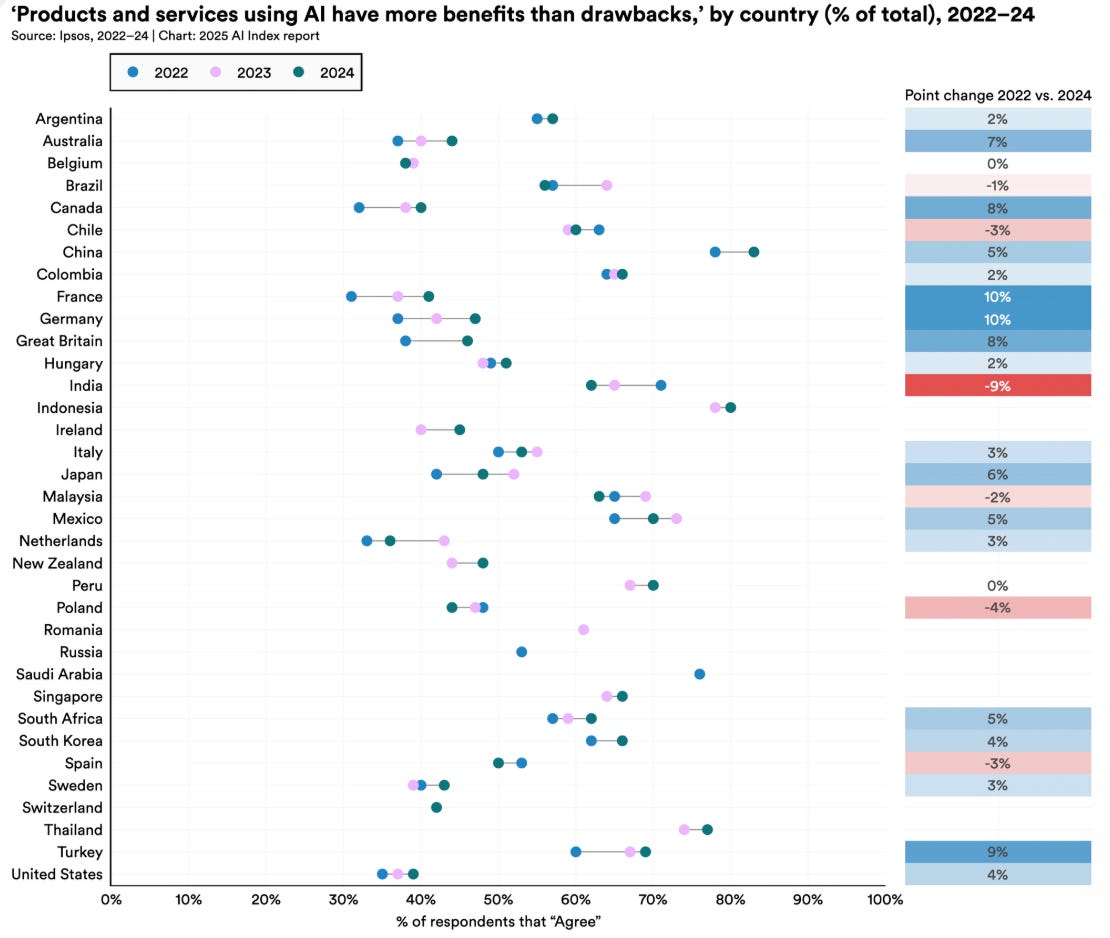

Further, simply “adopting AI,” as any large enterprise is eager to do, does not necessarily constitute successfully diffusing it. “Winning the AI race” is not merely using more AI but translating that use into economic and military advantage. This distinction makes quantifying the AI race even harder. Other metrics may indicate or predict successful AI adoption, like the number of AI integration-related job postings, programs for developing talent that know how to adopt AI, etc. A Stanford 2025 HAI report states that the percentage of the population in China that sees AI uses as “more beneficial than harmful” is more than double that in the U.S. Higher trust in AI may lead to quicker adoption.

Still, there are available metrics that indicate how much the U.S. and China are using AI, at least. One fraught indicator is simply a survey of businesses to understand how they use AI. A 2024 survey of decision makers in varying industries in each country found that 83% of Chinese respondents reported using GenAI vs 65% of American respondents (although, notably, the same survey suggests that U.S. organizations are ahead in terms of actually implementing mature GenAI tools – 24% of U.S. organizations have fully implemented GenAI technologies compared to 19% of Chinese organizations). As previously mentioned, according to an IBM study, 50% of Chinese companies have used AI versus just a third of American ones. These are imperfect indicators of AI use given differing interpretations of what using AI means and of AI itself.

Another indication of usage is how many tokens each country’s AI firms process. According to an article from Beijing tech media outlet QbitAI, as of the end of 2024, over 200 Chinese AI companies were each processing at least 1 billion tokens per day. As of July 2024, Tencent’s Hunyuan AI service alone reached a daily volume of 100 billion tokens.

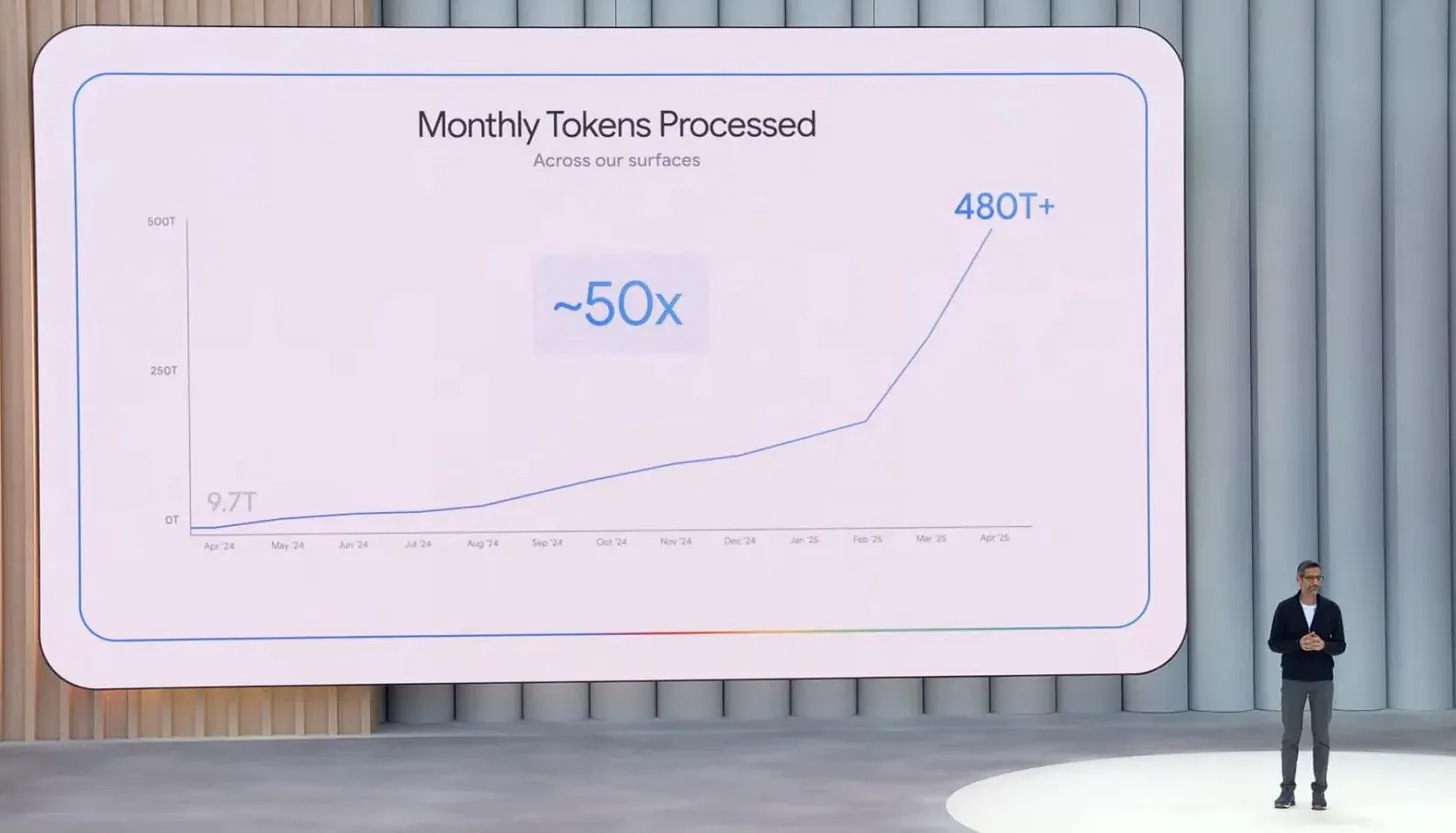

Available data about U.S. AI companies’ daily processed tokens suggest the U.S. uses significantly more AI. In July 2024, Google processed more than 300 billion tokens per day to Tencent Hunyuan’s 100 billion. Assuming similar growth patterns in AI adoption between the U.S. and China this past year, U.S. companies likely process many more tokens today. While we do not have updated Chinese data, we do have more recent data for American companies. Google alone announced that it processed more than 480 trillion tokens across all its platforms in April, which is ~16 trillion per day. Microsoft processed more than 1 trillion per day in April as well. Nathan Lambert, an AI researcher at the Allen Institute, estimates that OpenAI processes more tokens than Microsoft and fewer than Google. These usage numbers for Google, OpenAI, and Microsoft are far higher than Tencent’s, but they are 9 months more recent. That does not, however, account for any country-specific sudden changes in growth, which China may have benefited from after the release of Deepseek.

Of course, the number of tokens processed by the largest tech firms is not necessarily the strongest indicator of AI diffusion across the entire economy. Still, these companies serve the widest array of commercial and government customers, from startups to Fortune 500 companies. Use of their AI products paints a picture of AI use across various industries.

The Real DeepSeek Moment

While DeepSeek’s release earned comparisons in the U.S. to a “Sputnik moment,” in China, the “Deepseek Moment” meant a rush toward AI adoption. R1’s low cost and open source nature make it easy to integrate into a range of use cases. Further, the attention DeepSeek garnered worldwide made Chinese firms eager to adopt it quickly “as a signal of patriotism.” By March, Chinese firms were embedding Deepseek in “everything,” according to Kinling Lo at Rest of World. Lo highlights a few examples, including the provincial government of Shenzhen, Huawei’s Siri-like AI voice assistant, nearly 100 hospitals across China, and even the largest home appliance company in China.

The PLA took notice too. A recent report from Recorded Future’s Inskit Group found over 150 mentions of DeepSeek in procurement documents of the PLA and defense industry from early February to late May, the first four months after R1’s release. The report concludes: “The PLA very likely embraced DeepSeek following the company’s release of its V3 model in December 2024 and R1 model in January 2025.” That official procurement documents mentioned DeepSeek within only weeks of R1’s release indicates that the company has catalyzed a rapid pace of adoption.

View from the Top

Relative to the U.S. government, the Chinese government is known for pursuing national priorities through a top-down approach. This is also the case with AI. China developed its “New Generation AI Development Plan” in 2017 with the stated goal of leading the world in AI by 2030. The plan involved massive investments in AI infrastructure and led to designating “AI champions” in different verticals within the industry. Top-down guidance from the CCP about what initiatives to prioritize incentivizes ambitious local leaders throughout the country to pursue development in that field. Approximately 85% of Chinese government spending is at the local level rather than the federal level (compared to just 60% in the U.S.), meaning local government initiatives can drive significant demand. For example, the city of Hangzhou partnered with Alibaba to integrate AI in city governance under the “City Brain” project for traffic management and emergency response.

This ambitious effort provides a glimpse into how the Chinese government views its role in ensuring the diffusion of AI throughout the economy. Xi Jinping has made it an issue of personal interest, choosing AI strategy as his topic of choice for the Chinese Politburo session in April.

In May, Georgetown’s Center for Security and Emerging Technology (CSET) published a report about a large centralized effort in Wuhan to diffuse AI into “all aspects of daily life.” The effort is a collaboration between the Chinese Academy of Sciences’ (CAS) Institute of Automation, Huawei, and a Peking University consortium.

The effort, started in 2021, includes provisioning three layers – foundational (AI infrastructure including chips and other hardware), technical (AI models, including but not limited to LLMs), and applications (for the downstream beneficiaries such as local municipalities and various industries). Though vague, central to the effort is a “large-scale social simulator” that simulates “multiscale physical world and social complex systems,” which becomes “a tool of social governance.” The platform is essentially a digital twin for social governance that can “repeat tests in the field of social sciences, help explore intelligent social governance models, and improve the modernization level of national governance,” according to one of the project’s leaders.

This platform seems well suited for ever-closer population monitoring and control. Additionally, through platforms like this one and others in its surveillance regime, the Chinese government has and will continue to collect unique and valuable data about its large population that could be used to develop and deploy differentiated AI models going forward. While the effort’s stated objective is to help AI transform the whole economy, recent comments focused more on the social simulator, less on how the government would spur industry adoption beyond investing in infrastructure.

Whether central government efforts to drive industrial AI adoption will succeed is unclear. If the government’s primary focus in these efforts is censorship and control, rather than making society more efficient, it seems less likely that they will. Still, while the U.S. will almost certainly rely on improving models and innovative private sector startups to drive greater adoption of GenAI, the Chinese government sees itself as one of the main drivers of AI adoption within the PRC. These kinds of top down government initiatives, if executed well, could enable China to adopt AI more quickly than other nations relying on more traditional private market incentives. However, if executed poorly (for instance, by incentivizing the wrong kind of technology to be adopted), it could slow China’s AI adoption.

AI for the Chinese Government and PLA5

The Chinese government drives adoption not only through policy but also through its own purchasing power. An article translated by Jeff Ding provides insights into procurement orders from the Chinese government and State Owned Enterprises (SOEs) in the first half of 2024. In the first half of 2024, government and SOE customers put out 498 solicitations related to LLMs worth $186M (in a market worth trillions of dollars). The largest of these bids was for the “Eastern Data Western Compute” project, indicating that the Chinese government spends more on AI infrastructure than applications. Baidu, one of the companies that won the most bids, won contracts for AI applications or LLM access serving industries ranging from power grids, hospitals, financial services, waste management, and insurance.

AI is a top priority for the PLA. According to a U.S. Department of Defense (DoD) report, the PLA seeks “[to field] next-generation combat capabilities based on its vision of future conflict, which it calls ‘intelligentized warfare’ (智能化战争), defined by the expanded use of artificial intelligence (AI), quantum computing, big data, and other advanced technologies.” China’s strategy of Military-Civil Fusion (军民融合), which aligns the PRC’s defense industrial base to its civilian technology and industrial base, may help the PLA more rapidly integrate dual-use technologies, such as those listed above for “intelligentized warfare.”

The PLA Daily, the PLA’s official newspaper, has published several articles on PLA use cases of GenAI, suggesting that the PLA plans to use LLMs to generate intelligence briefs, analyze and extract key intelligence from large volumes of data, predict changes on the battlefield, provide battlefield situational awareness, and improve combat planning. China’s security forces have also published extensive AI research.

Thus far, the PLA has reportedly used DeepSeek’s latest AI models for a range of non-combat tasks, including in hospital settings and personnel management (supposedly, PLA military hospitals have used DeepSeek to provide treatment plans for military doctors). In mid-2024, reports surfaced that the PLA was experimenting with using Meta’s open-source Llama models for military tasks including “strategic planning, simulation training, and command decision-making.” The model was reportedly trained on Chinese military data, including over 100,000 military dialogue records. Reuters also reported that two researchers with the Aviation Industry Corporation of China (AVIC), a company with ties to the PLA, described using Llama 2 for “the training of airborne electronic warfare interference strategies.” These reports were released before Meta’s license allowed the US military to use Llama models for military uses. Further, patent activity suggests that Chinese defense companies are using military intelligence data (OSINT, HUMINT, SIGINT, GEOINT, and TECHINT) to train military-specific LLMs for intelligence tasks and military decision making.6 Procurement documents obtained by Recorded Future’s Insikt Group show that the PLA and affiliated entities have procured several GenAI based technologies including an LLM designed to analyze and generate reports based on Internet data and a tool to help conduct S&T intelligence.

Of course, PLA AI adoption is not without its challenges. In June 2024, CSET released a report analyzing the challenges that Chinese leadership faces when adopting AI for military use cases. Just like American military officials, PLA officials worry about the security and trustworthiness of AI. Unlike the U.S. military, the PLA has not fought a war in over four decades, leading officials to worry that the PLA does not have enough high-quality, real-world data to train AI systems. The PLA must rely on data collected during training exercises and synthetic data, which may not accurately represent real-world combat scenarios. PLA researchers also worry that GenAI will increase counterintelligence risks, as adversaries may use GenAI to create fake documents and deepfakes to mislead intelligence efforts.

Further, despite China’s stated civil-military fusion strategy, commercial technologies are not always seamlessly integrated into the Chinese government. Jeff Ding describes the government procurement market as “complex, opaque, and difficult to navigate.” Startups selling to the U.S. government often face similar challenges. Ding notes that “aside from Zhipu AI, China’s large model startups have made relatively few moves in the public procurement market…MiniMax, Baichuan, and 01.AI have not secured any bids in 2024.” Ding warns LLM providers that, while selling to the government can be lucrative, “These customers have a strong demand for customized solutions, making it difficult to quickly standardize and modularize AI products…Therefore, more companies choose To-Consumer as a breakthrough point.”

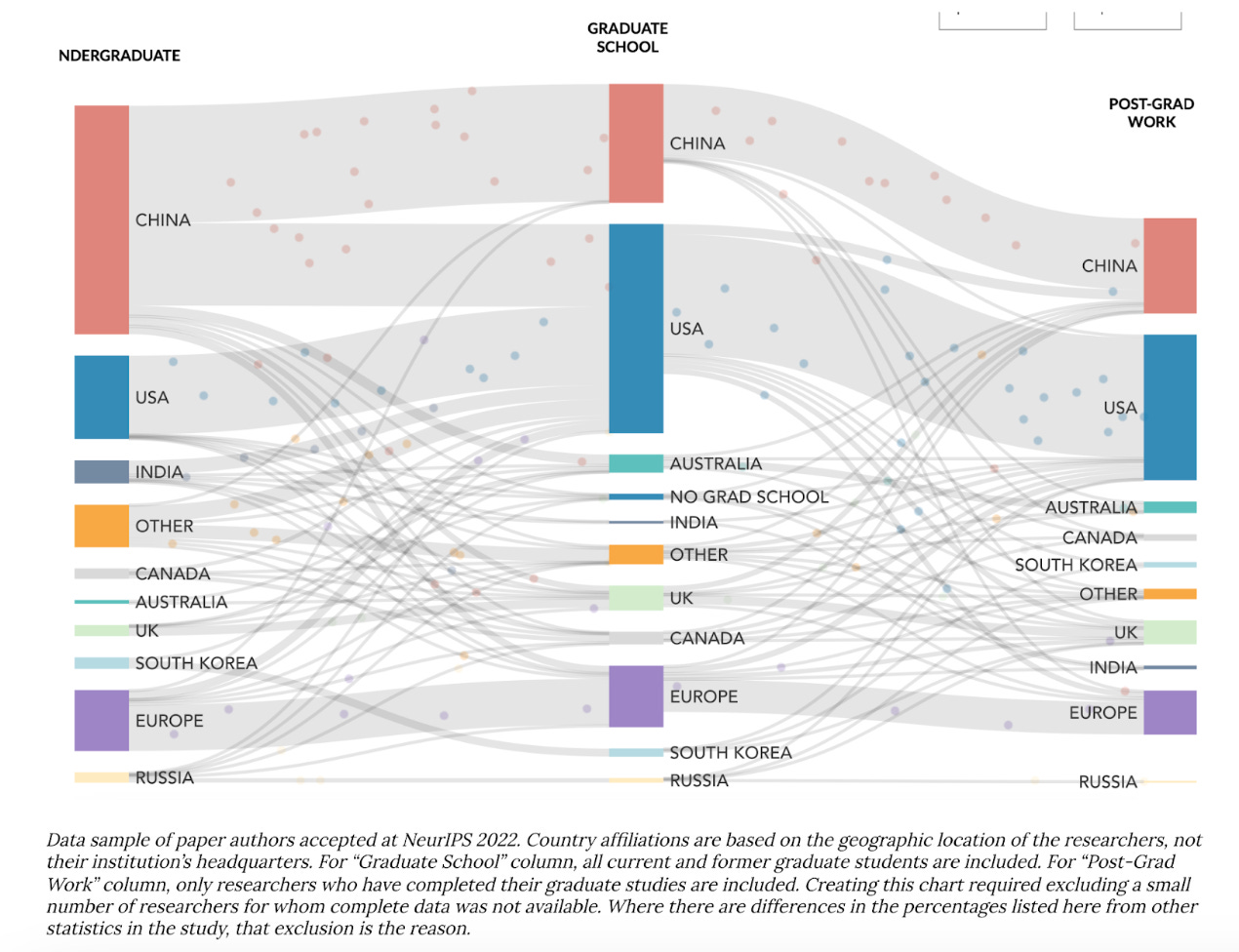

Talent

Having a strong talent base is needed to develop and diffuse AI throughout the economy. Many studies of China’s AI industry focus on top-tier expert AI talent. The Chinese undergraduates who pursue graduate work in AI, its most talented students, often leave to pursue that work in the U.S. Despite having far more undergraduates in AI, China has far fewer graduate students and post-grads than the U.S. The U.S. is clearly the most attractive place for AI experts.

However, expert talent is not necessarily the most important talent base for technology diffusion. Rather, as Jeff Ding argues, historically, the “secret sauce” for successfully adopting general purpose technologies was “located in the institutions that widened the base of average engineering talent [emphasis added] in a [new technology].” Scalable technology diffusion depends more on an army of capable mid-level engineers who can deploy technology than on a handful of top-tier experts conducting frontier research.

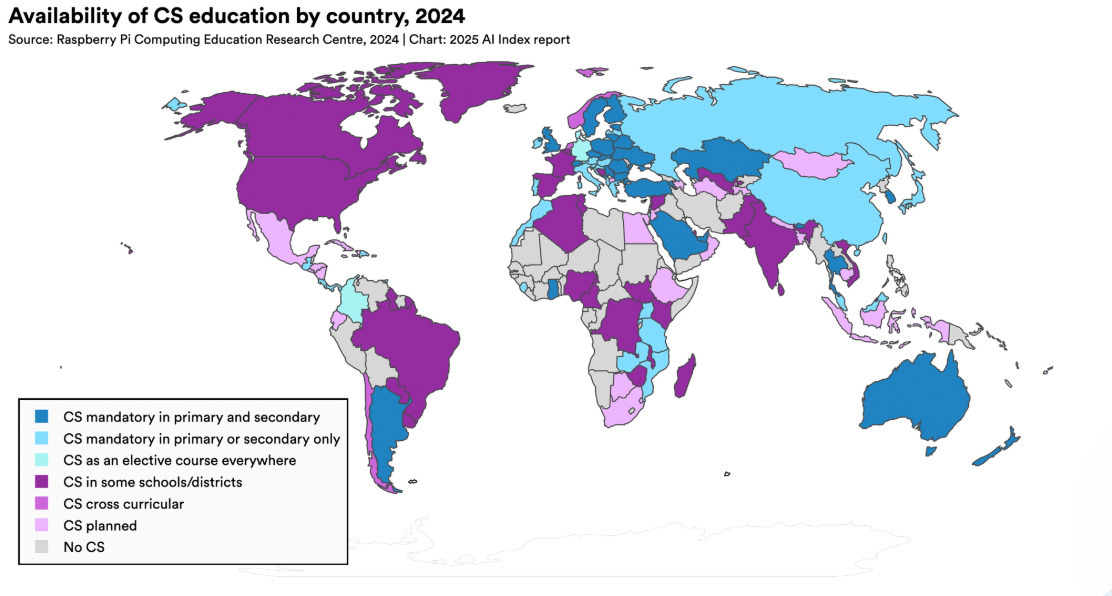

Here, the U.S. has an advantage – Ding notes that the U.S. has twice as many AI workers as China – but China may soon grow better equipped to rapidly and broadly adopt AI than the U.S. It graduates a much higher number of students focused on engineering than the U.S. each year, and according to a CSET study, in 2020, 41% of all Chinese students graduated with STEM degrees versus just 20% of American students. Whether these programs have the resources to teach the skills needed to win the AI diffusion race is unknown, but certainly China is investing heavily in developing the talent to compete.

Challenges for Chinese AI Diffusion

There are several factors that will likely limit China’s ability to diffuse AI effectively. First, there is significantly less high-quality Chinese language data available on the internet for Chinese AI models to train on. A lack of Chinese language data will make it more difficult for models to perform well on Chinese language activities, which will likely affect their utility across the Chinese economy and military.

Second, in stark contrast to the U.S. government, the Chinese government has imposed strict regulations on GenAI, requiring AI researchers to receive security reviews and licenses before public release out of concern for controlling misinformation and aligning content with state censorship rules. Thus far, the Chinese government has approved more than 100 AI models that meet government regulations. These restrictions are outlined in the “Interim Measures for the Management of Generative Artificial Intelligence Services,” and, among other requirements, require models to “uphold the core socialist values,” prevent racial discrimination, respect IP rights, and more. Infamously, popular Chinese models like DeepSeek’s R1 will not answer questions about politically sensitive subjects like Taiwan or Tiananmen Square. This kind of regulation and censorship poses several challenges. First, strict regulations slow the pace at which AI models can be published – and thus how quickly businesses can adopt them. Second, for national security use cases, having models that produce accurate, unbiased content is essential. A recent Recorded Future report on the PLA’s adoption of LLMs for intelligence suggests that censored models may provide biased intelligence analysis, ultimately making that analysis less useful.

Third, Chinese government regulations and restrictions make it difficult for people in China to access cutting-edge AI models developed outside the country. Both OpenAI’s and Anthropic’s models, widely considered to be the most cutting-edge models, are blocked in China. Thus, Chinese companies cannot easily take advantage of frontier models as they come out; instead, they must wait for Chinese companies to develop models with similar performance or find ways (e.g., VPNs) to bypass access restrictions placed on foreign models by both the Chinese government and model providers alike. As models become more advanced and capable of addressing a wider range of business or government tasks, U.S. entities with earlier access to those models may be better positioned to leverage them for economic or military advantage.

Fourth, for the time being, U.S. export controls on China’s AI sector will slow diffusion, by limiting the technology China’s AI sector has access to cutting edge chips and thus the market size for Chinese AI companies. Experts believe China’s semiconductor industry is at least five years behind the U.S. / Taiwanese semiconductor industry, in large part due to export controls. U.S. export controls prevent China from purchasing cutting-edge AI chips from American companies like NVIDIA. U.S. export controls also ban Chinese semiconductor companies from importing key technologies needed to develop cutting edge AI chips domestically, such as EUV7 lithography tools, limiting the performance of Chinese semiconductors. NVIDIA also maintains a strong moat in the form of its CUDA software and data center networking technology which competitors (American, British, and Chinese alike) have struggled to break.8 Chinese AI researchers will struggle to quickly train cutting edge models without cutting edge chips. Ultimately, this will slow the speed of Chinese AI diffusion, as it will take longer for Chinese customers to have access to highly performant AI models that work with Chinese language data and meet Chinese government regulations.

Additionally, U.S. regulations make it difficult for many crucial Chinese AI companies to sell outside the U.S., which will ultimately limit their market size and revenue potential and slow their ability to rapidly advance and diffuse their AI products. In May 2025 the Trump Administration issued guidance effectively banning the use of Huawei’s Ascend chips by suggesting that the use of Huawei’s Ascend chips “anywhere in the world” may be a violation of US export controls, arguing that these processors were allegedly developed and made using American technologies illegally. There is historical precedence that shows that being added to the U.S. entity list slows down Chinese AI companies’ ability to operate and grow, ultimately slowing diffusion. For example, when the U.S. added Chinese AI company SenseTime to the entity list in 2019, it significantly affected the company’s operations, causing the company to postpone its IPO and spurring short sellers to go after the company.

Conclusion

Without a doubt, building cutting edge AI models remains an important part of maintaining U.S. geopolitical competitiveness, but ultimately U.S. officials push for accelerated AI diffusion because they recognize that AI models will only be useful if they are actually quickly adopted at scale by enterprises and governments. The Pentagon’s (and the PLA’s) procurement processes may not be quite as complex as building Reinforcement Learning (RL) models for enterprises, but leveraging them to deliver real value through AI will be a significant undertaking.

Though the U.S. may not maintain its edge in AI model development indefinitely, its lead today is apparent. Its relative positioning in AI diffusion, however, is not. Still, while China may appear better poised to adopt this technology, it faces its own set of challenges, and likely still lags behind the U.S. in AI usage.

Commercially, the U.S. should lean into its free market system that will allow the best products to win. Enterprises operating in a competitive market will adopt AI products when they deliver real value. Still, the U.S. government should find creative ways to incentivize companies to share data openly, just as Xi announced that open data sharing between Chinese companies would be a priority. For example, Salesforce’s decision to cut other firms’ ability to query Slack data directly makes that valuable data unusable for any AI applications besides Salesforce’s. Consolidating access to AI development among fewer companies will degrade the quality of applications across the industry – thus decelerating AI diffusion and American competitiveness.

Leaning into the free market system also means, perhaps paradoxically, allowing U.S. companies to access Chinese models. Particularly since Chinese models are often cheaper and thus catalysts for adoption, banning Chinese models altogether could significantly hamper AI diffusion efforts. If China continues to grow the capability gap in open source models, advantages of using its models for various applications would be inevitable due to their cost and open licensing. The U.S. cannot afford to ignore these advantages. The U.S. government must secure access to leading AI models while educating users about potential CCP-driven censorship risks and actively mitigating security vulnerabilities that could be exploited by Chinese threat actors.

Broadly, the U.S. government should continue investing in AI infrastructure, talent, research, and adoption. It should also refrain from passing legislation that would hamper the development and adoption of American AI technology.

The U.S. government should prioritize procuring more AI-based products when possible, which would help stimulate commercial development of the technology. The DoD in particular must prioritize accelerating its adoption of AI for strategic advantage – for instance by improving its command and control systems. Additionally, the Pentagon should find ways to rapidly adopt AI for non-mission-critical tasks like compliance and procurement paperwork. As former DoD GenAI lead Glenn Parham outlines, there are several simple ways DoD can accelerate AI adoption including purchasing licenses for basic enterprise AI products like Microsoft Copilot (which would immediately enable millions of DoD employees to access GenAI tools), provisionally authorizing9 the managed model services across cloud providers for all impact levels (enabling developers and operators alike to access AI model APIs across the whole DoD network), and pre-committing GPU-specific cloud spend (say, a few hundred million dollars) to each cloud provider in order to incentivize cloud providers to move GPUs to their government environments. The PLA will pay close attention to these DoD adoption efforts, as it already has; the DoD should learn lessons from how the PLA is adopting AI, too.

Broad access to AI talent will be necessary for both commercial and national security customers to adopt AI. The U.S. government must cultivate that talent by integrating AI literacy into education programs far more broadly and far earlier. The government should continue to provide funding for AI research at the high end and should invest in AI upskilling and vocational training at the low end, to build a strong base of engineers who understand AI. Additionally, the U.S. should continue to incentivize foreign students studying computer science and AI to study and live in the U.S., and the U.S. government should reform immigration laws to make it easier for a much larger number of skilled workers with AI or computer science experience to stay and work in the U.S. permanently.

These are all practical, tactical steps. To develop a broader strategy that addresses AI diffusion, the U.S. government needs to better understand its relative standing in the race to adopt AI by developing metrics that assess the state of global AI diffusion. How can we best measure whether we’re accruing the benefits of AI? In what categories does the U.S. better leverage AI, and in what categories has it fallen behind China? These questions will help the U.S. direct its efforts toward policies and initiatives that can help it leverage AI for economic and military advantage.

Critically, the future of AI diffusion will also influence the future of AI development. After widely adopting computer vision and facial recognition technology for robotics, manufacturing, and surveillance use cases, China became a leader in developing computer vision and facial recognition algorithms. Technology diffusion incentivizes researchers to continue advancing the state of the art and allows technologists to incorporate rapid feedback and build up large, unique datasets to improve the underlying technology.

The AI race is not just about technological supremacy: it’s about the systems, cultures, and incentives that enable technology to be deployed at scale. China’s top-down mobilization strategies may offer more speed and cohesion but face hurdles in data quality, hardware constraints, and regulatory censorship. The U.S., by contrast, leads in model innovation and has the advantage of a dynamic private sector, yet its fragmented infrastructure and limited government procurement efforts could slow adoption. The outcome of this race will hinge less on who builds the best model and more on who deploys them faster, more widely, and with greater strategic purpose.

Today, the impact of AI on global economies and militaries remains highly uncertain. Uncertain too is the U.S.’s relative progress in adopting AI on both fronts. To prevail, it must translate its technological edge into operational advantage across its economy, government, and military before its window of leadership begins to close.

As always, please reach out if you or anyone you know is building at the intersection of national security and commercial technologies. And please reach out if you want to further discuss the ideas expressed in this piece or the world of NatSec + tech + startups. Please let us know your thoughts! We know this is a quickly changing space as conflicts, policies, and technologies evolve.

INDOPACOM = Indo-Pacific Command.

For those interested in an in depth overview of the state of China’s AI industry, we highly recommend checking out Recorded Future’s report “Measuring the US-China AI Gap.” We reference this report heavily in this piece.

Baidu offers the Qianfan “large model platform” (“千帆大模型平台”), Tencent Cloud’s offering is called TI platform, Alibaba Cloud’s offering is called Model Studio, and Huawei’s offering is called ModelArts.

Prior to ChatGPT, the DoD’s largest AI-related project was Project Maven, which used computer vision to analyze aerial imagery. Few commercial Silicon Valley technology companies worked on the project, with the exception of Google whose employees ultimately protested the contract.

For those interested in an in-depth overview of the PLA’s research and writings on GenAI, we highly recommend checking out Recorded Future’s report “Artificial Eyes: Generative AI in China’s Military Intelligence”.

For more details on the specifications of these models, see the aforementioned Recorded Future report “Artificial Eyes: Generative AI in China’s Military Intelligence” which provides a detailed summary of the patents.

EUV = Extreme Ultraviolet

For an excellent overview on NVIDIA’s business model and technology, I highly recommend reading Tae Kim’s book The NVIDIA Way and listening to the Acquired podcast’s multi-part series on the company.

A provisional authorization is a formal cybersecurity approval issued by DISA under the Risk Management Framework (RMF) or FedRAMP programs, allowing cloud service offerings (CSOs) to be used by DoD components. It signifies that a cloud service has met a defined set of security requirements and is provisionally approved for handling government data at a specified impact level. The provisional authorization makes it much easier for developers to get an ATO to use these models.

Note: The opinions and views expressed in this article are solely our own and do not reflect the views, policies, or position of our employers or any other organization or individual with which we are affiliated.

Made some of these same points in this podcast with Kevin Frazier: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=fLn9IQbUdec

This is very interesting and weird timing. I just started substack recently and I wanted to create a platform for debate. My first topic is AI regulation in the US. This was a great challenge to my original thoughts and understanding of it!