Follow the Money: What the Pentagon's Budget Data Tells Us About AI and Autonomy Adoption

AI and Autonomous Systems Spend: A $25 Billion Question

Department of Defense (DoD) officials, venture capitalists (VCs), and startup founders alike love to tout the DoD’s innovation initiatives to field cutting edge artificial intelligence (AI) and autonomous systems technology. Former DEPSECDEF Kathleen Hicks launched the DoD’s billion dollar Replicator initiative to deliver thousands of relatively low-cost, “attritable” autonomous systems. Just last week Vice President JD Vance was photographed flying FPV drones developed by Neros, an American drone startup.

However, those working in defense innovation know that despite paying lip service to the importance of adopting new technologies like AI and autonomous systems, the DoD has been slow to buy and field these systems at scale. Even initiatives like Replicator got off to a slow start engaging with cutting-edge startups – the first tranche of Replicator funding went to purchasing Aerovironment Switchblades, 15-year old, $50,000+ loitering munition with limited autonomy functionality developed by a legacy defense contractor.

So, I decided to dig into the numbers. How much does the DoD actually budget and spend on AI and autonomy? Who’s winning these contracts? Are venture-backed startups gaining ground or still stuck on the sidelines?

Thanks to a wave of new tools that make government contracting data easier to explore, we no longer have to guess. I used my favorite, Obviant, to pull the data.1 Here’s what I found.

Overall DoD AI and Autonomous Systems Budget

First, I set out to see how much the DoD actually budgets for AI and autonomous systems each year. To do this, I used Obviant to analyze the “J-books”, detailed documents within the President’s Budget Request (PBR) to Congress that break down the DoD’s funding requests by military department. The J-books detail what the DoD is buying, how much it costs, how many units are planned, and when delivery is expected — a goldmine for tracking real DoD budgeting intent.

Overall, the DoD budgeted $25.2B for programs incorporating artificial intelligence and autonomous systems in Fiscal Year 2025 (FY25), about 3% of the DoD’s total $850B budget. The majority of this funding ($21.8B) is allocated to research, development, testing, and evaluation (RDT&E), 15% of the total $143.5B RDT&E budget, while only $3.4B is designated for procurement, about 2% of the total $167.5B procurement budget.2 I’ll note that these numbers are not perfect – the $25.2B number is based on a keyword search and includes budget items that incorporate AI or autonomy in just one small part of a larger program or in future program planning. Note that former SECDEF Llyod Austin’s summary of the DoD’s FY25 stated that only $1.8B was set aside explicitly for artificial intelligence.

The overall budget for these technologies has more than tripled over the past six years, rising from around $7B in 2019.

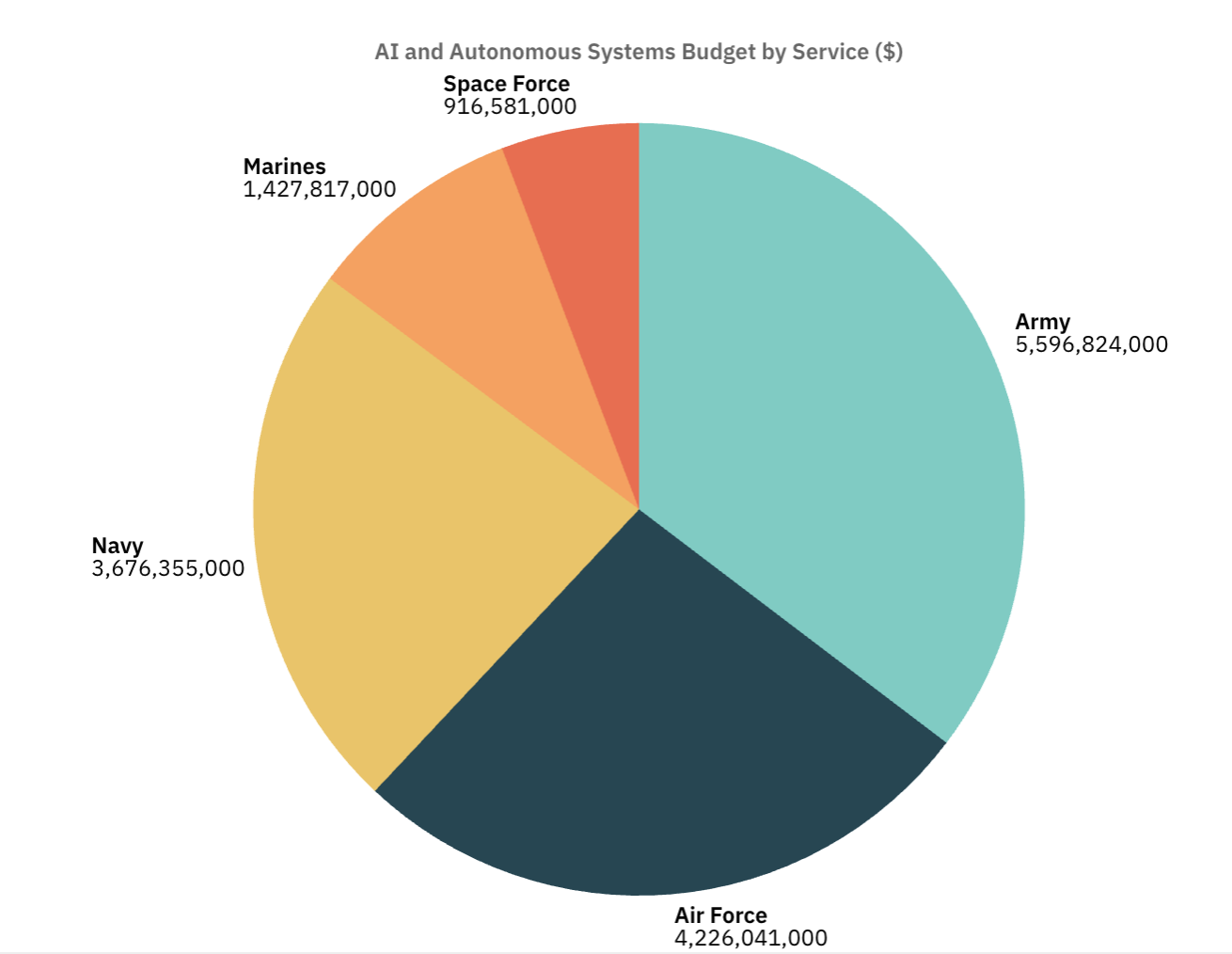

DoD AI and Autonomous Systems Budget by Service

In the FY25 budget, the Army allocated approximately $5.6B for AI and autonomous systems, followed by the Air Force and Space Force at $5.14B,3 and the Navy and Marine Corps at $5.1B.4

The majority of the DoD’s budget is split up across the military services (Army, Air Force, Marine Corps, etc.) and contracted through their respective Program Executive Offices (PEOs) and department laboratories (e.g. AFRL, NRL, ARL, etc.). Startups aiming to sell AI and autonomous systems to the DoD should align their solutions with the services’ existing programs that already have budget allocated. Below is a non-exhaustive list of some of the DoD’s major budgeted projects related to AI and autonomous systems:

DoD Fourth Estate and Combatant Commands AI and Autonomous Systems Budget by Agency

Close to half of all budget requested ($9.9B) comes from the Fourth Estate5 and combatant commands (particularly Special Operations Command and Cyber Command) rather than from the services. The Fourth Estate, COCOMs, and intelligence community likely spend even more on these technologies than this number suggests, but many of their contracts are not publicly disclosed. Specifically, the Office of the Secretary of Defense (which includes innovation-focused organizations like Defense Innovation Unit, DIU, and the Chief Digital and AI Office, CDAO), Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA), and Defense Threat Reduction Agency (DTRA) have all made significant budget commitments to AI and autonomous systems. I’ve broken out the money spent by the Fourth Estate by agency here (I separated out CDAO, which runs major AI-related programs like JADC2,6 from the rest of OSD):

AI and Autonomous Systems Contract Value by Company

Now that we know how much the DoD is budgeting, the next question is: who is actually winning contracts to develop AI and autonomous systems for the DoD? First, I’ll note that I purposefully excluded more legacy unmanned systems from this analysis.7 I wanted to focus my analysis on the next generation of autonomous systems that leverage AI to operate vs. decades old, expensive remote controlled unmanned systems like the Predator drone, MQ-9 Reaper, and AAI RQ-7 Shadow. I also excluded most contracts related to the F-35 program, which has some AI / autonomous elements, but is largely a human-controlled fighter jet. Additionally, this data does not include contracts awarded to companies through OT consortia.8

Legacy IT systems integrator (SI) Booz Allen Hamilton holds a dominant position in AI-related DoD contracts, largely thanks to its major support role with CDAO’s Advana platform and its provision of on-site contractor personnel (i.e. “butts-in-seats”). Perhaps unsurprisingly, Palantir and Anduril are also among the top recipients of prime DoD contracts focused on AI and autonomous systems.9 Several other startups have made it into the top fifteen AI and autonomy contract recipients: C3.AI, Shield AI, Scale AI, Vannevar Labs, Saildrone, and Skydio. Other major players include more traditional IT SIs like ECS Federal, which has worked on a number of AI-related programs including Project Maven. More traditional robotics hardware developers like Teledyne Flir, General Dynamics, and Foster-Miller (a subsidiary of Qinetiq) have also won significant contracts developing robotic systems.

Major Contract Value for AI and Autonomous Systems Related Programs by Company

While startups have scored some notable contract wins, a closer look at the prime contractors on major AI/ML and autonomous systems related programs of record like ABMS, JADC2, and Robotic Combat Vehicle (RCV) reveals that traditional defense primes and large systems integrators still dominate. Much of the DoD’s spend on startups is still coming from organizations with special acquisition authorities like SOCOM (several of Anduril and Palantir’s largest contracts are with SOCOM) and innovation focused organizations like CDAO and DIU.

Below is a list of a few major AI / ML and autonomous systems related programs and their largest prime contractors (certainly non-exhaustive) . Even Project Maven, one of the DoD’s most famous (or infamous) AI programs is largely dominated by traditional defense primes, with the exception of Palantir:

There does seem to be some hope that the DoD is starting to change its buying patterns to buy more cutting-edge AI and autonomous systems technology from companies leveraging commercial technologies. In the past year, Palantir has won several additional large AI-focused contracts, namely a $178M contract for Tactical Intelligence Targeting Access Node (TITAN) ground station system, the Army’s next-generation deep-sensing capability enabled by AI, and a $480M Army contract for Maven Smart Systems, a platform which uses AI to analyze sensor data to modernize battlefield operations like targeting, logistics planning and predicting supply needs. Additionally, in September CDAO announced that it was planning to re-compete its 10-year, $15B Advana contract, and the new administration is pushing for Advana to become a formal program of record. This re-compete could replace legacy SIs like Booz Allen and open the door to more innovative small businesses, startups, and companies leveraging commercial AI and data analytics technologies. Similarly, although Replicator’s first tranche of funding was won by a legacy prime (Aerovironment), subsequent tranches of funding are going to newer VC-backed startups like Anduril, which was selected for its counter-UAS capabilities, and other undisclosed startups and non-traditional vendors building unmanned maritime surface vehicles.

AI Contracts by Service

Breaking out contracts by service is a tricky data science problem. Luckily, USAF Lt. Col. Chris Berardi, the Deputy Director of the MIT / USAF AI Accelerator, was kind enough to share some previous analysis he’s done looking at AI/ML contract value by service. Note that this data does not include contracts related to autonomous systems, and he completed his analysis before FY24 ended, so the FY24 data is only partial year data. The Air Force has obligated significantly more to AI/ML contracts than the other two services, as has the Fourth Estate (the Fourth Estate saw a bump in spending in 2020 and 2021 due to COVID-related initiatives).

The data also reveals that the Air Force is a real leader in working with small businesses and startups to develop and acquire AI-enabled products. The Air Force has significantly more SBIRs10 related to AI/ML than other services, and Air Force AI/ML SBIRs appear to have consistently higher transition rates compared to the other services. The Air Force isn’t just experimenting with AI/ML research, they’re also transitioning some of that technology into real procurement contracts through sole-source Phase III SBIR contracts.

Takeaways and Recommendations

As I’ve written about before, AI and autonomous systems are reshaping warfare, and the DoD must accelerate adoption in order to stay competitive and maintain credible deterrence. AI and autonomous systems are critical enablers for the DoD’s core objectives: increasing lethality, saving lives, and cutting costs. In particular, the DoD should prioritize adopting AI and autonomy to improve logistics optimization, electronic warfare, precision mass, and back office automation. Commercial technologies developed by non-tradition vendors, especially VC-backed startups, will need to be part of the solution, as they offer adaptable, rapidly deployable tools to address real DoD challenges.

The data shows that VC-backed startups building AI and autonomous systems are making inroads with the DoD, but the field is still dominated by traditional defense primes. Programs like Advana and Replicator hint at a shift toward more innovative, non-traditional vendors, but it’s early days.

What should DoD do to accelerate the speed of AI and autonomous systems adoption?

When evaluating the budget for these technologies, the DoD should adopt a strategy of structured divestment, systematically identifying legacy programs and systems that are “unneeded, obsolete, unproductive, unsecure and un-auditable.” These programs should be decisively sunsetted and their budget reallocated toward emerging technologies that address the same needs. For example, legacy programs focused on deploying costly electronic warfare sensors that require manual analysis by human experts could be largely replaced by low-cost, off-the-shelf software-defined radios enhanced with machine learning algorithms capable of autonomously analyzing radiofrequency (RF) data – increasing lethality, saving lives, and cutting costs.11

In order to field these technologies quickly enough to deter our adversaries in a relevant timeline (i.e. before 2027), it will be crucial for the DoD to prioritize agile acquisitions processes. The new administration appears to be on the right track: in March, SECDEF Pete Hegseth issued a new memo directing all DoD components to adopt the software acquisition pathway12 as the “preferred pathway for all software development components of business and weapon system programs” and use commercial solutions opening and Other Transaction authority to speed up the procurement of digital tools for warfighters.” Now, it is up to the Pentagon leadership to ensure this directive is followed across the whole organization.

Additionally, the DoD must accelerate the transition of promising technologies from RDT&E efforts to full-scale deployment. One way to accelerate this transition is through meaningful reform of the SBIR program. During his testimony to the U.S. Senate Committee on Small Business and Entrepreneurship, my colleague David Rothzeid proposed a number of potential reforms to improve SBIR transition rates and make SBIRs more accessible to venture-backed startups like making SBIR contracts firm-fixed price by default and cost-reimbursement by exception; providing additional financing to first-time recipients to meet the NIST-mandated Cybersecurity Maturity Model Certification (CMMC) standards, as well as the “authority to operate” (ATO) and “facility clearance” (FCL) approvals; instituting and enforcing a “shot clock” for award notification and contract award; strictly enforce use of open interoperability standards; implementing and maintaining a standard set of proposal formats for the SBIR/STTR program; and creating an avenue for due process and require agency feedback to companies that were passed over for the program.

Further, the DoD could increase the speed of AI and autonomous systems adoption by reforming security processes like the ATO and CMMC compliance processes, which startups and DoD officials alike often cite as a major barrier to adopting new technologies. The FY25 NDAA included language to improve the ATO process. Specifically, it directs the DoD to develop a policy requiring DoD officials to accept security analysis and artifacts of a cloud capability that has already been authorized by another DoD official or component, known as "presumptive reciprocity,” (previously, vendors needed to get separate ATOs for each DoD organization they sought to work with). This reform is a good start to ATO reform, and it is crucial that DoD implements these policies swiftly to accelerate the speed of adoption of new software capabilities. Similarly, Michael Duffey, the new administration’s nominee to be the next undersecretary of defense for acquisition and sustainment, told lawmakers that he will review a number of other security requirements if he’s confirmed. Specifically, he stated that he will review CMMC requirements, and he will “actively explore” the feasibility of multi-use SCIFs13 and other shared resource models to reduce that burden for small firms and facilitate their access to classified information.

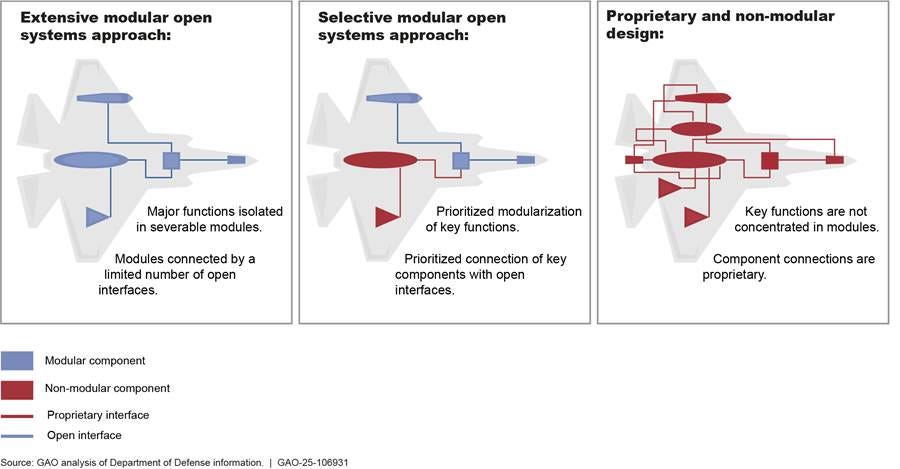

On the technology side, the DoD should continue advancing open, standardized, and modular software architectures for its hardware platforms, while also prioritizing greater interoperability across both hardware and software systems. In many cases, the DoD does not need to (and should not) fully scrap exquisite hardware systems it has already purchased. Instead, it should look to augment those systems with AI and autonomy software.14 Standardized and modular software architectures enable faster integration of new software and make it easier to tailor applications across different platforms.15

The DoD is actively working to make it easier for vendors to build on top of other vendors’ platforms. In 2019 the DoD issued a memo, signed by the Secretaries of the Army, Air Force, and Navy, mandating the use of the Modular Open Systems Approach (MOSA) “in all requirements, programming and development activities for future weapon system modifications and new start development programs to the maximum extent possible.” MOSA aims to improve interoperability, accelerate innovation, and reduce costs by enabling plug-and-play integration of components from different vendors – avoiding vendor lock-in and making it easier to upgrade systems over time. While the DoD has made some progress in successfully enforcing MOSA, a recent GAO report shows that there is still significant room for improvement. The GAO reviewed 20 recent programs and found that 14 of the 20 programs it reviewed reported implementing a MOSA to at least some extent. However, “most programs did not address all key MOSA planning elements in acquisition documents, in part, because the military departments did not take effective steps to ensure they did so.”

Similarly, as outlined in a Defense Innovation Board (DIB) report (and as I’ve written about previously), the DoD has an “API problem.” In the commercial sector most modern software products have easy to use application programming interfaces (APIs) that enable data integration between different systems. However, much of the software used by the DoD lacks high quality APIs, making it difficult to integrate applications developed by different vendors and causing significant duplication of effort. One horror story relayed to me, for instance, involved DoD personnel manually re-entering thousands of lines of data from one service’s ERP into another service’s. To advance AI and autonomous systems development, the DoD must streamline integration across data stores with an “API-first approach,” as recommended by the DIB report, in order to enhance the capabilities of AI-enabled platforms.

What should startup do to help the DoD accelerate AI and autonomous systems adoption?

Startups should lean into their strengths: building software that runs on top of exquisite hardware and harnesses the proprietary data it generates, while using inexpensive, off-the-shelf hardware components to reduce costs and scale quickly. Where possible, startups should look to sell into existing programs and budget lines that would benefit from improved AI and autonomy software, like those outlined above. Identifying opportunities for structured divestment, where legacy programs can be replaced 1:1 with more advanced AI-enabled and autonomous alternatives, can help align their offerings with DoD priorities. Partnering with defense primes can provide access to contracts, integration pathways, and credibility within the acquisition process.

Additionally, to accelerate the speed to deploy systems, startups should also become intimately familiar with DoD processes and standards like the DoD’s cybersecurity requirements, the ATO process, supply chain requirements, and MIL-SPEC and MIL-STD performance requirements. Further, it will be critical for startups to understand the computing hardware limitations for the systems they plan to deploy onto; many DoD hardware systems are not equipped to run complex software. For instance, a Tesla Model S car has 10 times the computing power of an F-35 Joint Strike Fighter. By aligning with these strategies, startups can effectively position themselves as enablers of next-generation defense capabilities. Startups should plan their tech deployments accordingly and provide customers with off the shelf compute hardware to augment legacy systems when necessary.

In an era of accelerating geopolitical competition and rapid technological advancement, the DoD can no longer afford to treat AI and autonomy as experimental or secondary. These are not “future” capabilities, they are today's operational imperative. Our adversaries aren’t waiting to develop and deploy these technologies. Just a few months ago, as part of its push towards “intelligentized warfare,” the Chinese People’s Liberation Army (PLA) demonstrated its new Intelligent Precision Strike System which uses real-time data from UAVs16 to autonomously model the battlefield, track targets, devise strike plans, distribute firing information, and execute follow-up strikes. To outpace adversaries like China, the Pentagon must urgently shift from incremental pilots to scaled deployment, from closed architectures to open interoperability, and from legacy vendors to agile, venture-backed innovators. The window to act is narrowing, and the cost of hesitation is strategic irrelevance.

As always, please reach out if you or anyone you know is building at the intersection of national security and commercial technologies. And please let me know your thoughts! I’m always happy to chat about the world of NatSec + tech + startups. I know this is a quickly changing space as the administration rolls out its new initiatives, and I know that this kind of data analysis is far from perfect, as the underlying data itself is far from perfect.

Finally, I want to say a huge thank you to both the Obviant team and Lt. Col. Chris Berardi for spending time with me to help me understand how best to use and analyze DoD budgeting and contracting data.

DISCLAIMER: I will note the data I present here is certainly not perfect. Much of the data Obviant pulls from is manually entered by humans, so it is not super clean data. This data is also lagging – DoD contracting data is not made public until several months after the initial contract is awarded. Additionally, I extracted this data using a keyword search for terms like “artificial intelligence,” “machine learning,” “robotics,” “autonomous systems,” and others, so I undoubtedly missed some key budget and contract items that didn’t explicitly use the keywords I plugged in. Further, I often surfaced budget and contract items that may have mentioned one of my keywords once, briefly, as part of a much larger and more expensive project. I did some manual data editing to remove large, less relevant contracts and budget items and manually added in some key contracts that were not included in the initial data set. My goal is to provide useful insights into overall DoD budgeting and contracting trends to highlight where real opportunities exist for startups building AI and autonomous systems, and how the Department can improve its approach to funding and procuring these technologies. Please let me know your thoughts! I’m very open to feedback on how to improve this kind of analysis in the future.

I combined the Air Force and Space Force, as they share an overall budget.

I combined the Navy and Marines as they share an overall budget.

The Fourth Estate refers to the Office of the Secretary of Defense agencies and activities that are not part of the military services. Examples of these agencies include: DLA, DTRA, DIU, CDAO, SCO, DISA, among others.

JADC2 = Joint All Domain Command and Control. JADC2 is a DoD-wide initiative designed to improve the integration and interoperability of U.S. military forces across all domains and services. The goal is to provide a unified, cohesive approach to military operations, enabling faster and more efficient decision-making and response times. For more, see the DoD’s Summary of the Joint All-Domain Command and Control Strategy.

A note on my methodology (which I’m sure is imperfect): first, I ran a keyword search to find all DoD contracts that had words like “artificial intelligence,” “autonomous systems,” “robotics,” etc in the title. Then I also manually added in certain contracts that I knew were relevant, but did not include these keywords (ex: I manually added Palantir’s Gotham, TITAN, and Maven contracts, Shield AI’s V-BAT contracts, Anduril’s Lattice, Roadrunner, and Anvil contracts, a number of C3.AI’s contracts, etc). Again, I’m sure this does not provide a perfect complete picture of the state of the DoD’s AI/ML and autonomous systems contracts, but hopefully it’s able to show general trends.

OT consortia are relationships between government sponsors and collections of traditional and non-traditional vendors, non-profit organizations, and academia aligned to a technology domain area.

Note, the chart displayed below only shows prime contracts, not subcontracts.

SBIRs, or Small Business Innovation Research Grants, are grants given to small businesses to work with the DoD on innovative technology. There are three phases of SBIRs: Phase I SBIRs are relatively low lift and only require the startup to produce a white paper on a particular technology. For Phase II SBIRs, the funding amount can be anywhere from $500K to $1.5M and with it an increase in expected deliverables. Phase II SBIRs can be transitioned into Phase III SBIRs which are much larger sole source contracts. As evidenced by the data, SBIR transition rates are relatively low – significantly more money is put into Phase II SBIRs than Phase III SBIRs. If the goal of a Phase I or II SBIR is to transition to a sole source production contract like a Phase III, then most AI/ML Phase I and II SBIRs are not reaching their goals.

For more on how AI and cheap off the shelf sensors are revolutionizing electronic warfare, check out my interview with the founders of Distributed Spectrum on the Mission Matters Podcast.

From DefenseScoop: “The department’s Software Acquisition Pathway, or SWP, was set up during the first Trump administration under then Undersecretary of Defense for Acquisition and Sustainment Ellen Lord as part of a broader push for a so-called Adaptive Acquisition Framework that enables the department to procure software differently than it buys hardware. Programs on that pathway are not subject to some of the encumbrances associated with the Joint Capabilities Integration and Development System and major defense acquisition program designations.”

SCIF = Sensitive Compartmented Information Facility. A SCIF is an area, room, group of rooms, buildings, or installation certified and accredited as meeting Director of National Intelligence security standards for the processing, storage, and/or discussion of classified information.

For example, as we discussed in our recent interview with the founders of Distributed Spectrum on the Mission Matters Podcast, Distributed Spectrum is able to deploy their ML algorithms on top of the DoD’s existing sensor platforms.

For a concrete look at how software layered on hardware with standardized, modular architectures can drive major impact, I recommend reading this piece by Austin Gray and Artem Sherbinin on the future of software-defined warships in the Navy.

UAV = unmanned aerial vehicle

Note: The opinions and views expressed in this article are solely my own and do not reflect the views, policies, or position of my employer or any other organization or individual with which I am affiliated.

This is excellent, thanks Maggie.

Feel free to peruse the budget via my tool (free), defenseprograms.app, maggie. If you have any issues let me know.