How SBIR Spurs Outsized Economic and National Security Gains – Time to Double Down

SBIR success stories from startups that turned small grants into hundreds of millions in impact

On September 30, 2025, government authorization for the Small Business Innovation Research (SBIR) program officially lapsed and has not yet been re-authorized. While federal agencies can continue funding current awards already made under SBIR, which are still valid and ongoing, agencies cannot issue new SBIR solicitations or make new awards under those programs until Congress reauthorizes the program. Currently, lawmakers are at an impasse over whether to reauthorize the program in its current form. After wrapping up final negotiations last week, Congress plans to officially release and vote on the National Defense Authorization Act (NDAA), the primary bill that sets the budget and priorities for the Department of War (DoW). The vote might also unjam the stalemate for the SBIR program re-authorization and reform.

In light of the ongoing debate around the SBIR program, we wanted to share a few “SBIR Stories” from startups who have used SBIRs the right way, to fund development of technology that ultimately has outsized returns in national security and commercial sectors.

If you have followed my blog over the past couple years, you have probably seen me mention the SBIR program many times. While the program is far from perfect, SBIRs have become an integral part of the national security innovation ecosystem, providing startups with grants that enable them to access U.S. government customers and fund technology development. Started in 1982 and administered by the Small Business Administration, SBIRs provide seed funding to small businesses across the majority of federal agencies which enables them to de-risk their core technology and build out initial prototypes at an earlier stage of development than potential customers or private sector investors may be willing to invest. Failure to re-authorize and reform this program would be a loss for both the startups vying for federal R&D and federal agencies who depend on SBIR to accelerate mission success from cutting edge technology companies.

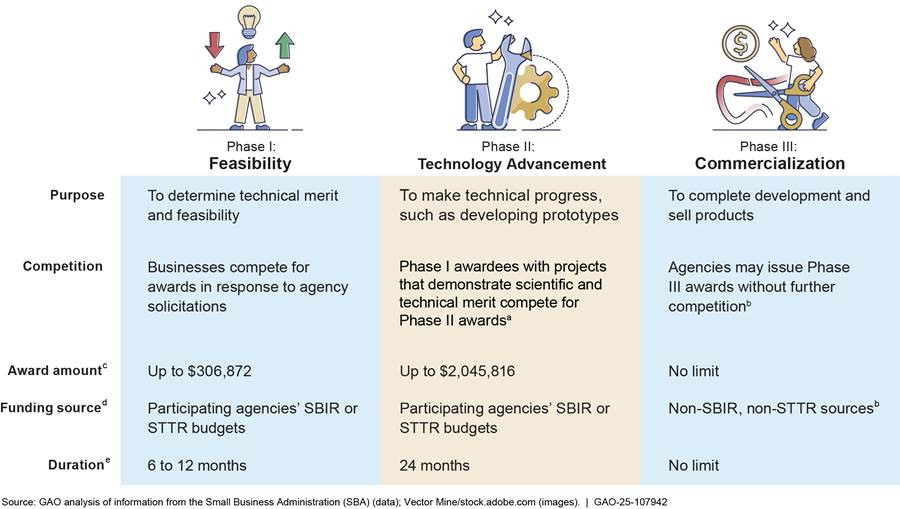

The SBIR program is structured in three phases. Technologies are developed, tested, and evaluated during Phase I and II agreements. Phase III is the final and most important phase of the program. In Phase III, the government transitions well-performing Phase I and II technologies to follow-on production contracts (which can be worth tens or even hundreds of millions of dollars) to scale successful technologies. Very few SBIR awardees make it to Phase III – one Naval Postgraduate School study suggests that only 16% of SBIR companies transitioned beyond Phase II, leaving most stuck in perpetual R&D.

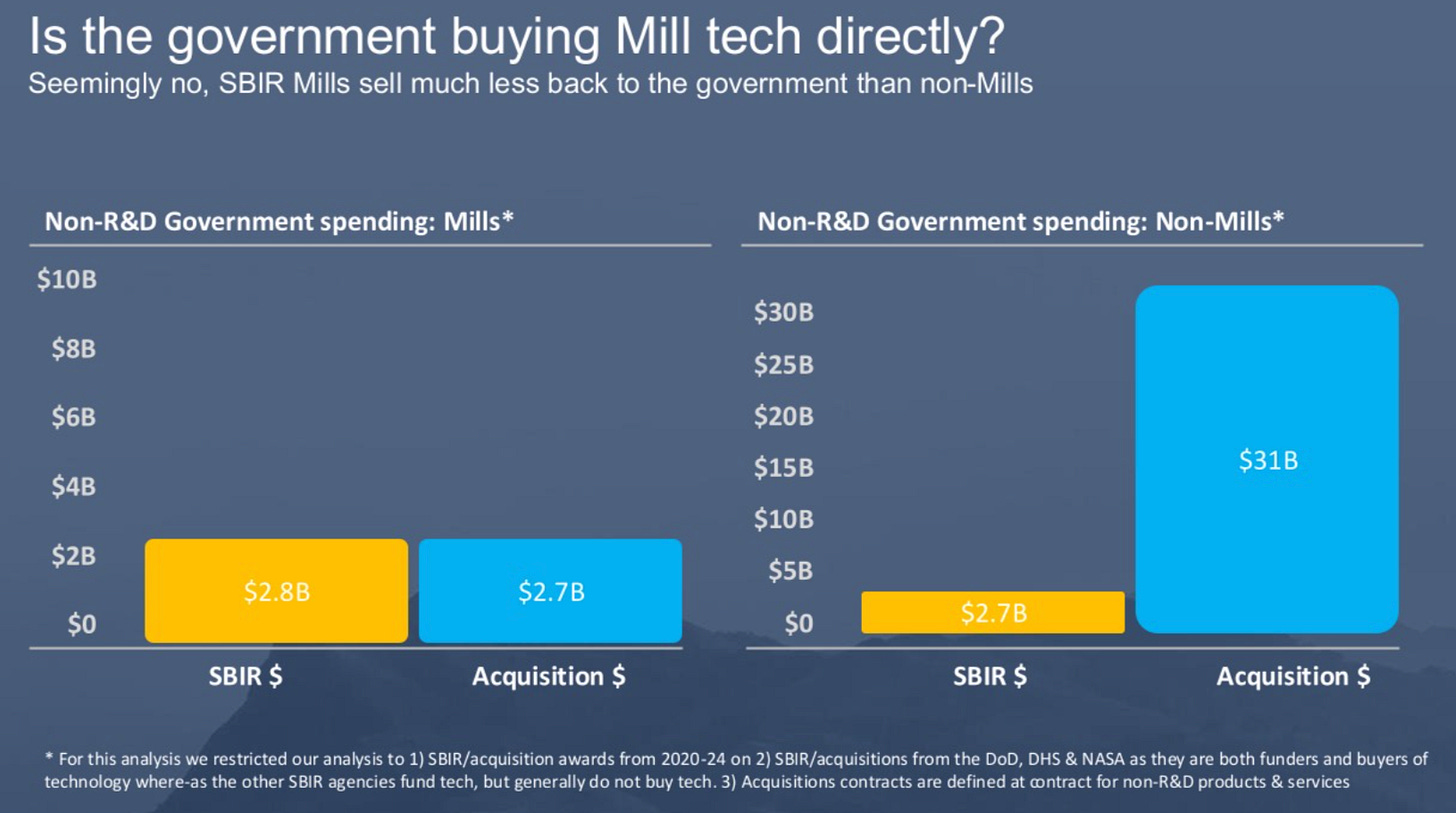

The Investing in National Next-Generation Opportunities for Venture Acceleration and Technological Excellence (INNOVATE) Act, proposed by Senator Joni Ernst, is at the heart of the debate over SBIR reauthorization. Among other initiatives, the INNOVATE Act seeks to implement common sense reforms to improve the efficiency and effectiveness of the SBIR program by limiting the amount of SBIR funding going to “SBIR mills”, a small class of “multi-award winners” (MAWs) whose business models depend on winning SBIR contracts instead of maturing into self-sustaining companies. Some SBIR mills win close to $100M worth of SBIRs each year – a Government Accountability Office report found that of nearly 7,000 SBIR companies, the top 22 alone secured 17% of all DoW Phase II funding between 2011 and 2020. For more on the details of SBIR reform, see David’s Senate testimony and his two part article series on the subject.

Source: Geoff Orazem LinkedIn

Despite the waste clearly present in the current program, it is still essential for the SBIR program to be reauthorized (preferably with reform in place). SBIRs are an invaluable resource for early stage startups looking to sell to national security customers. When executed well, SBIRs do far more than provide grant funding: they help foster a dynamic ecosystem of national security innovation, creating communication pathways for DoW stakeholders, startups, and private capital allocators to work together towards national security objectives. These relationships and communication pathways are part of the scaffolding of modern defense innovation; if the program lapses for too long, that infrastructure will erode and take years to rebuild.

First and foremost, SBIRs provide startups with non-dilutive R&D funding that can help them de-risk early technology before obtaining customer revenue or private investment. Second, SBIRs give startups direct access to U.S. government customers and real operational insights they would otherwise struggle to obtain – while simultaneously giving government stakeholders visibility into cutting-edge technologies they might not encounter through traditional channels.

Finally, the U.S. government can use SBIRs to create a market demand signal for particular products and technologies to spur private sector investment. Many VC investors (our firm included) look to see whether startups have won any SBIRs as a sign of government interest in a technology area. Of course, not all SBIRs are created equal, but with the right technical point of contact, SBIRs can indicate that there is real government interest in purchasing a technology, which can lead to larger government contracts down the line.1 By attracting outside capital, the government effectively shares R&D costs with the private sector (rather than bearing them entirely as it does with traditional prime contractors) resulting in a more efficient and scalable model for developing new capabilities.

The U.S. government should view SBIRs as early stage seed investments, similar to early stage VC investments, that have the ability to provide outsized returns in the form of: 1) larger production government contracts won, 2) large commercial contracts won, 3) private capital fundraises, 4) technology de-risked, and 5) jobs created. We contend that small SBIRs worth just a few hundred thousand or few million dollars should create tens or even hundreds of millions of dollars of value.

When the SBIR program works, it can work very well. There are real examples of companies starting with small SBIRs going on to transition those SBIRs to sole source production contracts and ultimately to programs of record. For instance, according to data from Obviant (a Shield Capital portfolio company), Anduril has won more than $36M in Phase I and II SBIRs which helped pave the way to over $4B in government contracts, nearly $7B in private investment, and a workforce of roughly 7,000 employees – all within less than a decade of its founding. Several of Anduril’s SBIRs have specifically transitioned to programs of record – for example, Anduril’s space program began as a Phase II SBIR from the Space Force in 2021, transitioned to a Phase III, and ultimately transitioned to a full program of record for Space Force’s Space Surveillance Network.

As Congress weighs the future of the program, it’s worth grounding the debate in real world stories that show the power of SBIRs when they are used effectively. Below are several examples of early-stage companies that used small SBIR awards to unlock meaningful technology development, major government contracts, large private capital fundraises, and substantial private-sector growth.

Unstructured

Location: Loomis, CA

Number of Employees: ~70

VC Funding Raised: $68M

Unstructured.IO works to solve a crucial problem for both U.S. government and commercial organizations looking to leverage AI: making unstructured data AI-ready. Unstructured has built a novel, open source data preparation platform that is able to transform unstructured data (like images and video) into structured data (like JSON) that can be used for AI. During its first year of existence, in 2022, Unstructured won its first CRADA2 and its first Phase I SBIR, worth ~$74K, from the U.S. Air Force. The next year, Unstructured continued to expand their work with the U.S. military, winning three more Phase II SBIRs, each worth ~$1.2M, to build data tooling for the government, and in early 2024, less than two years after the company’s founding, Unstructured won a TACFI.3

The return on those initial SBIR dollars is clear: since winning that initial $74K SBIR Phase I in 2022, Unstructured has raised more than $68M in VC funding, hired more than 70 employees, and has expanded its open source product to users across almost 1000 DoW agencies and 200,000 commercial companies (including 82% of Fortune 1000 companies)! Within the next 6 months, they expect their revenue (from both government and commercial customers) to be several orders of magnitude larger than that first SBIR contract. Just a small investment from the DoW has led to a tremendous amount of value created for both military and non-military customers around the world.

Unnamed AI Company

Location: Boston, MA

Number of Employees: ~50

VC Funding Raised: $50M+

An AI company we work with, who asked to remain anonymous due to the sensitivity of their work, builds AI developer tools that support U.S. government, defense industrial base, and commercial customers. During its first year of operation, this company landed a small USAF Phase I SBIR, worth ~$150k. A few months later, they converted their Phase I into a Phase II worth ~$1.3M, and then, just a few months after that, it advanced to a sole source Phase III worth tens of millions of dollars.

Since winning their initial $150K SBIR Phase I, the company has raised more than $50M in VC funding, hired more than 50 employees, landed millions in commercial contracts, and transitioned from winning R&D contracts to winning a sole source production Phase III contract.

Seasats

Location: San Diego, CA

Number of Employees: 49

VC Funding Raised: $20M

Seasats builds autonomous, unmanned surface vessels for U.S. military and commercial customers. In 2022, two years after the company was founded, Seasats won its first SBIR Phase I, worth ~$250k, from the National Science Foundation. In September 2025, Seasats transitioned to win a sole source SBIR Phase III IDIQ with a $89M contract ceiling from NIWC Atlantic to provide boats to the U.S. Marines Corps, ~$2M of which has been funded so far.

Since winning their initial $250K SBIR Phase I, Seasats has raised more than $20M in VC funding, hired close to 50 employees, landed millions in additional DoW contracts, and transitioned from winning R&D contracts to winning a sole source Phase III contract.

Apex Space

Location: Los Angeles, CA

Number of Employees: 201

VC Funding Raised: $522M

Apex Space builds satellite vehicles for commercial and government customers. They take a modular, productized approach to satellite manufacturing that enables speed and price transparency in a market known for delays and cost overruns. Apex won their first SBIR in 2023, a Phase II award from the Space Development Agency (SDA) to develop a rapidly produced, configurable satellite bus. Over the next year, they won additional SBIRs across the Air Force, Space Force, and SDA culminating in a 2024 $45.9M STRATFI award, driven by the DoW’s need for a capability absent from the commercial market and unmet by legacy providers – one that Apex alone showed it could deliver at operational speed to provide commercial speed not currently available in the satellite manufacturing marketplace.

Along its journey Apex has parlayed its SBIR and STRATFI success to raise more than $500M in follow-on private capital funding. It has also buoyed its government contracts with private sector bookings which dwarf those of their government funding. Recently Apex performed a ribbon cutting ceremony for its second manufacturing facility and has hired over 200 employees.

Starfish Space

Location: Tukwila, WA

Number of Employees: 65

VC Funding Raised: $53M

Starfish Space builds small servicing spacecraft designed to dock with unprepared satellites, extend their operations, handle inspection and relocation missions, and dispose of them at their end of life. Their “Otter” vehicle emphasizes autonomous rendezvous and docking, enabling missions that historically required much larger, expensive systems. Starfish won their first SBIR, worth $50K, in 2021 and progressed through several Phase I and Phase II awards and eventually a TACFI. In 2024, Starfish secured a $37.5M STRATFI from Space Systems Command to build, launch, and operate an Otter vehicle for an augmented-maneuver servicing mission in Geostationary orbit (GEO).

In parallel, Starfish progressed through Phase I and Phase II awards with NASA and ultimately won a competitively-sourced $15M NASA Phase III contract for the “SSPICY“ mission, which will use Otter to inspect several inactive U.S. satellites in low Earth orbit (LEO). On the commercial side, the company has signed Otter mission contracts with satellite operators who saw the US Government traction as an important proof point; the first of these was with Intelsat (now SES) for a multi-year GEO life-extension mission.

Since winning their first $50K SBIR in 2021, Starfish has raised more than $50M in VC funding, hired close to 100 employees, and landed millions in sole source government and commercial contracts.

Taken together, these stories underscore what is at stake. When applied as intended, the SBIR program converts modest early-stage grants into scalable dual-use capabilities, competitive private markets, and meaningful national security outcomes. Allowing the program to languish without reauthorization or overdue reform risks stalling the very innovation pipeline the U.S. depends on. The path forward is clear: preserve SBIR, strengthen it, and ensure that the next generation of high-impact companies can follow the same trajectory demonstrated here.

As always, please let us know your thoughts, and please reach out if you or anyone you know is building at the intersection of national security and commercial technology.

Organizations like SpaceWERX have seen particular success transitioning SBIR companies. Through PIA partnerships, SpaceWERX educates and supports companies through the SBIR process from winning their first award to transition, securing early buy-in from end customers on SBIR topics, leveraging their resources to ensure those users have a real stake in the outcome.

CRADA = Cooperative Research and Development Agreement. A CRADA is a partnership that lets a federal organization and a non-federal partner collaborate on R&D, sharing expertise and resources while giving the partner preferential rights to resulting IP.

TACFI = Tactical Funding Increase. A TACFI is a DoW program that uses SBIR dollars to match private investment dollars or other government investment dollars at a 1:1 ratio.

Note: The opinions and views expressed in this article are solely our own and do not reflect the views, policies, or position of our employer or any other organization or individual with which we are affiliated.

It would appear that most of the exemplars had one or a small number of SBIRs in a relatively short period of time (<10 years); those would not appear to me to be "SBIR mills" in the colloquial sense of a company who repeatedly wins contracts over long periods of time (decades in some cases) and yet who transitions few if any efforts. The examples may be exceptions rather than the norm -- and might provide clues as to what makes a "useful" SBIR candidate for the department.