A Playbook for U.S. Startups Selling Defense Tech in Europe

What does it take for American startups to sell into European defense markets?

Ten years ago, European defense spending hit rock bottom. Today, it’s a booming market. The stakes could not be higher for European democracies; Europe has now seen first hand what happens when a failure to prioritize military strength causes deterrence to break down. Tomorrow (October 1), European heads of state will meet in Copenhagen to discuss how to strengthen Europe’s common defense as well as increase support for Ukraine.

Russia has not only invaded Ukraine, which is not in the EU1 or NATO,2 but has also increasingly violated the airspace of European NATO allies such as Estonia, Poland, Romania, and Norway, with a number of3 Russian incursions into NATO airspace occurring in the last month alone. On September 19, three Russian MiG-31 fighter jets violated Estonian airspace and remained there for a total of 12 minutes, leading Estonia to trigger Article 44 consultations. Just nine days earlier, Poland requested Article 4 consultations after 19 Russian drones entered Polish airspace, and several days before that, Romania’s F-16s “came close” to taking down Russian drones that had breached the country’s airspace when attacking Ukrainian infrastructure near the Romanian border. In late September, several unidentified drones flew over Denmark, causing multiple Danish airports to shut down; while the Danish government has not publicly confirmed who conducted the operation, many suspect Russian state actors were behind the incursions. Just yesterday (September 29), Denmark banned all civilian drone flights after more drones were sighted near Danish military bases.

For American national security startup founders, the real question is no longer if they should try to sell into Europe, but how. I asked my friend Anna Strumpel to collaborate on this piece with me to offer a playbook for how American startups should approach European defense markets. Anna was the second hire on the European business development (BD) team at Shield AI, an American defense startup focussed on drones and AI pilots, where she closed $55M in European deals, and is now the Head of European BD at a stealth European defense tech startup, so she is intimately familiar with what it takes to sell cutting edge defense technology to the European defense ecosystem.

Source: @Gerashchenko_en on Twitter

Recognizing the growing threat from Moscow’s expansionist ambitions, Europe is racing to re-build its armies, with startups and commercial technology at the center of that transformation. In Ukraine, military forces have used unmanned surface vessels to destroy or disable one-third of Russia’s Black Sea fleet, Starlink to communicate without traditional telecommunications infrastructure, and FPV5 drones to take out Russian tanks. Major European powers like Germany and Poland are dramatically expanding their defense budgets and re-arming to prepare for a potential modern ground war. In March, Germany’s Bundesrat approved the creation of a new €500B fund to spend on infrastructure and defense by easing borrowing rules, ending decades of German fiscal conservatism and restrictions on defense spending; in May, German Chancellor Friedrich Merz announced that he plans to create Europe’s most formidable conventional Army; and in June Berlin announced plans to spend close to €650B on defense by 2030 (more than double its current military spending). Meanwhile Poland has almost doubled its defense spending as a share of its GDP and is pushing to increase the number of Polish military personnel by 50% by 2035. Overall, in 2024 the European Union (EU) spent €343B on defense – up 37% from 2021.

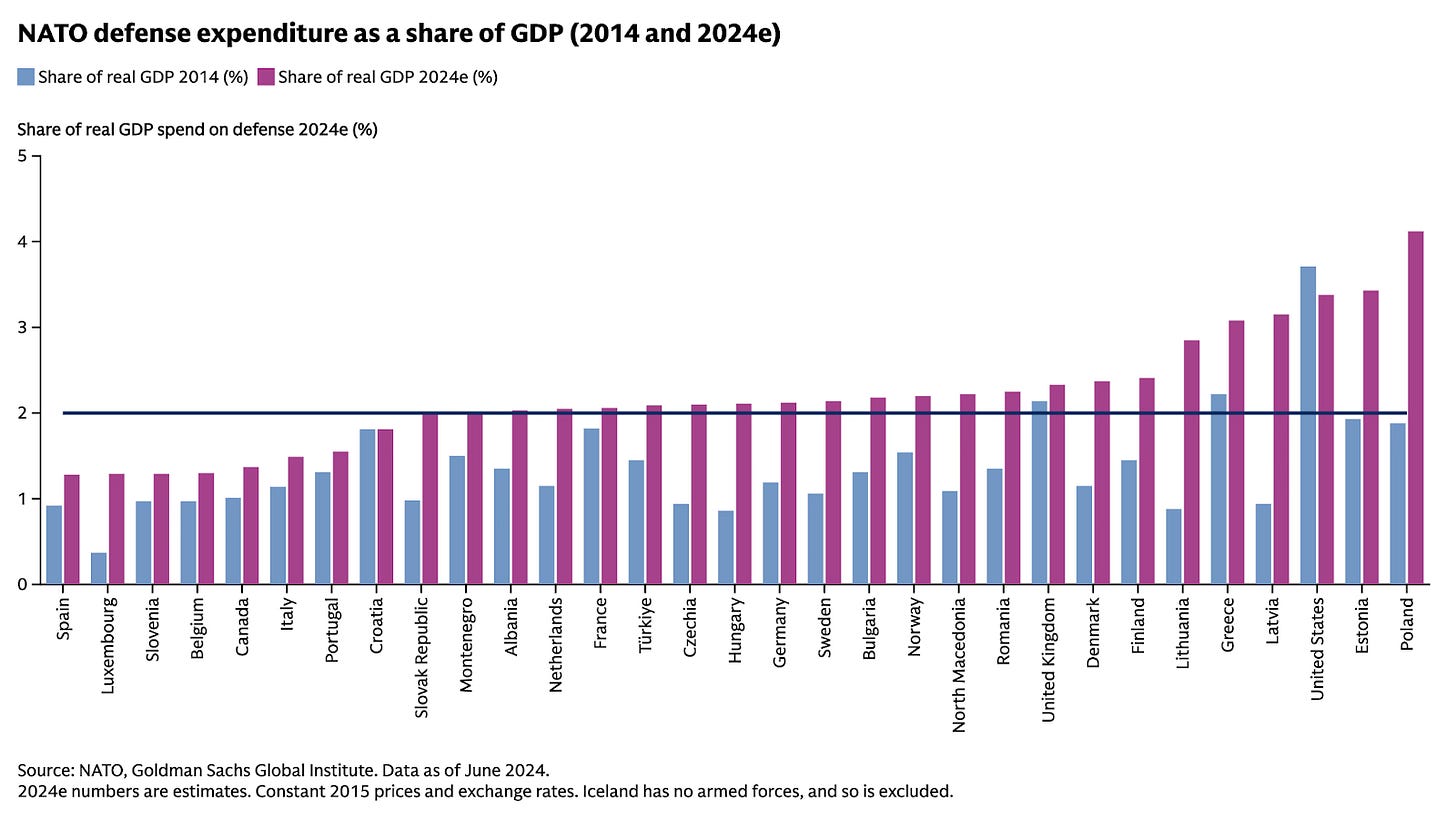

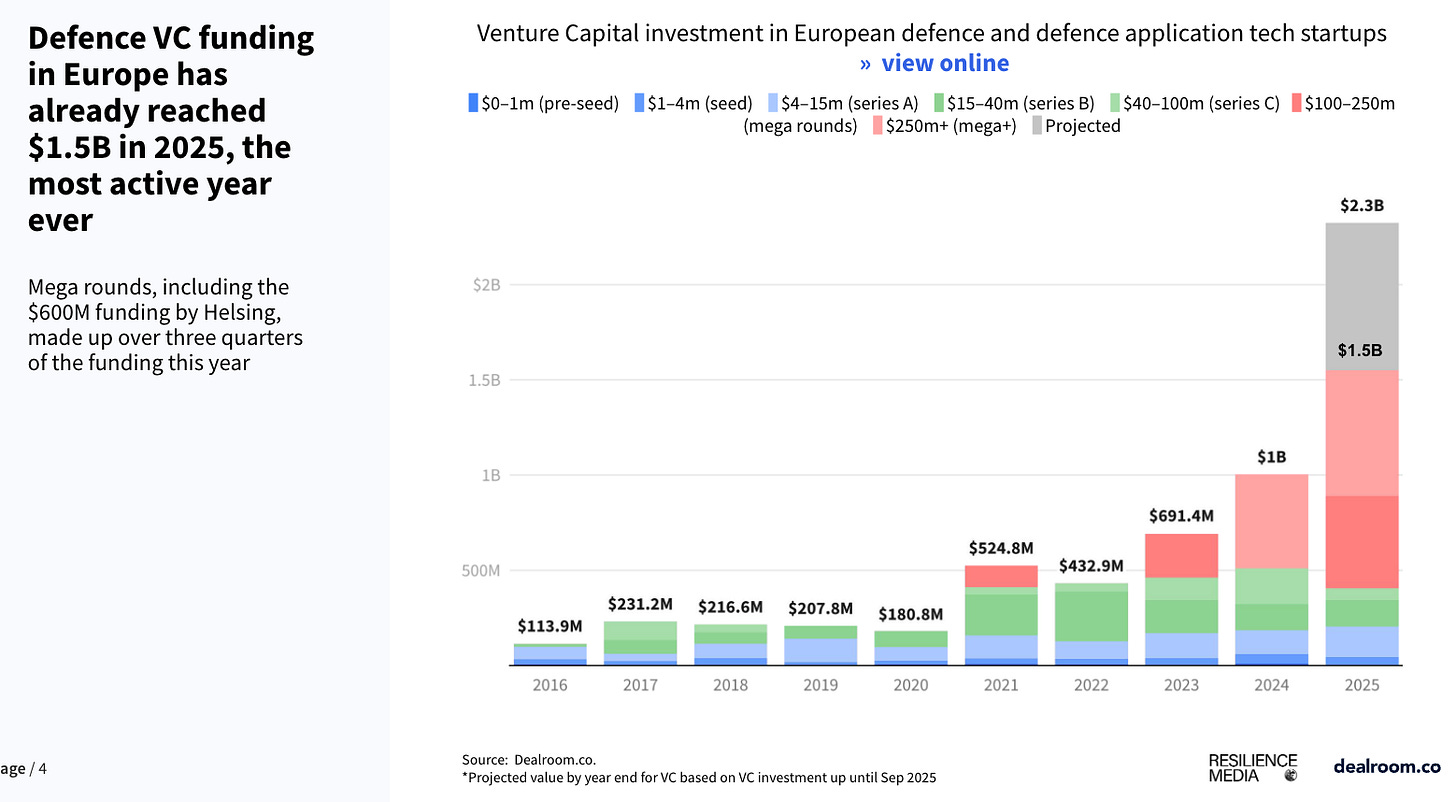

However, until recently, Europe was not a major forward leaning player in defense technology. In 2014 European defense spending hit an all time low as a percentage of GDP: collectively, in 2014, European NATO allies and Canada spent just 1.43% of GDP on defense spending (in contrast, the U.S. spent 3.71% of GDP on defense that same year). Not only was Europe spending less on defense in general, they were also investing less on cutting edge defense technologies: from 2005 to 2017, European defense R&D spending fell from 5% to 3.5% of total defense spending. Private markets mirrored this lack of public defense spending: in 2019, only $207.8M of VC investment in European startups went to defense related technology startups (compared to ~$1B invested in American defense related startups that same year). In fact, until recently, many European VC firms were prohibited by their limited partners from investing in defense at all.

Source: Dealroom State of Defence Tech 2025

As Russia has become more aggressive, leaders in the U.S., which has provided a security guarantee to Europe since the end of WWII, have emphasized the need for European countries to take more responsibility over their own security. In an August interview, Vice President J.D. Vance stated, “No matter what happens, no matter what form this takes, the Europeans are going to have to take the lion’s share of the burden [of defending Ukraine]. It’s their continent, it’s their security, and the President has been very clear – they’re going to have to step up.”

Europe’s commitment to spending more amid the U.S.’s intent to pull back from the continent will drive tremendous growth in the European defense sector and create opportunities for startups. Of course, for me, as an American venture capitalist investing in national security, these market trends raise the question: what does all of this European defense spending mean for American startups? How can American startups best penetrate the European market – and is it a market worth going after at all in the first place? Most American startups I meet are curious about the European defense market, but few (outside of a handful of exceptions) have devoted significant resources to understand and serve that market.

Why should American startups try to sell to the European defense market in the first place?

Selling into the European defense market is a way for startups to expand their defense TAM, speed up time to market, and get real battlefield testing experience. With Ukraine as the primary theater where the West is under direct attack – and with multiple Russian incursions into NATO airspace occurring over the past several weeks – this is the arena where defense companies can prove they are able to move the needle where it matters most.

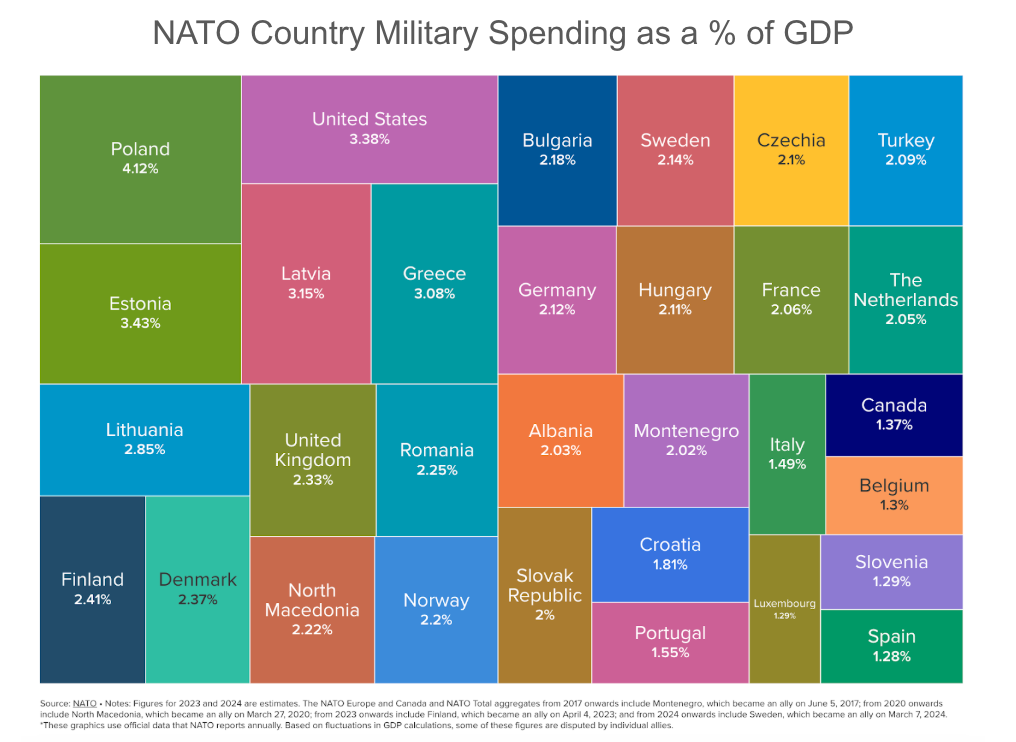

While the U.S. spends by far the most money on defense of any country, startups can dramatically expand their defense market size by targeting the rapidly growing European market. In 2024, European NATO allies and Canada spent a total of $506B on defense – led by Germany ($97B), the United Kingdom ($82B), France ($64B), and Poland ($35B) – and contributed an additional $111B in bilateral aid to Ukraine. In contrast, that same year, the U.S. spent $967B on all defense spending and $123B on bilateral aid to Ukraine. If Europe follows through on its defense spending pledges, the size of the European defense market could quickly catch up to the American market within the next decade.

Improving the state of their militaries and adopting the new technologies needed to remain competitive in a future conflict are literally existential for many European countries, driving European defense budget growth. Eastern European countries like Poland, Romania, and the Baltics cannot afford to move slowly in adopting technologies like drones, cybersecurity, and electronic warfare (EW) resistant communications and navigation, as they face direct threats from Russia if they do not adopt these new technologies.

In March 2025, the EU announced its “Readiness 2030” plan, which aims to unlock an additional €800B in European defense spending by 2030. The plan loosens EU fiscal rules to allow EU member states to spend an additional €650B on defense over the next four years and establishes a €150B fund providing loans to purchase arms.

Further, at a NATO summit in June 2025, NATO members agreed to increase member states’ overall defense spending target from 2% to 5% of GDP. For context, today, on average, NATO countries (including the U.S.) spend about 2.7% of GDP on defense – the U.S. spends 3.38% while European and Canadian NATO allies spend 2.02% (up from just 1.54% in 2019). European leaders have also recognized the importance of cutting-edge technology on the future battlefield: since the war in Ukraine began, European defense R&D spending increased from 3.5% to 3.9% of all defense spending.

In addition to growing defense spending, some European defense agencies, which are much smaller than the U.S. DoD, can move much more quickly than the U.S. DoD. The U.S. defense market moves at a speed commensurate with the size of its bureaucracy – the absolute fastest any company has won a large scale U.S. government contract is 3 years (with the help of the Defense Innovation Unit, in 2020, Anduril won its first program of record, PoR, with DHS6 in just under 3 years, the fastest transition to PoR in 70 years).

Historically, European defense agencies have struggled to quickly procure innovative technology at scale, relying on performative, yet ineffective “innovation theater,” and hampering vendors with unreasonable requirements (ex: years ago when trying to sell drones to European customers, some customers would institute requirements for drone “noise proofing” in order to prevent drone flight noise from bothering wildlife in nature protection zones). However, faced with an existential threat, European countries have learned to be more agile, rapidly acquiring solutions off the shelf without requiring vendors to jump through as many arduous hoops.

A striking example of exceptionally rapid European defense procurement driven by the Russia threat is Germany’s recent procurement of several loitering munitions systems. Historically, German defense procurement has moved notoriously slowly: there are close to 12,000 employees working at Germany’s BAAINBw7 alone (BAAINBw is a German government procurement agency responsible for equipping the German armed forces with modern weapon systems), and German military procurement processes can take over a decade. Yet, driven by the urgency of the conflict in Ukraine, where loitering munitions have played a prominent role, the German government procured the OWE-V loitering munitions from the newly founded European startup STARK within just 10 months of the company’s founding, alongside the HX-2 loitering munitions from the four-year-old German startup Helsing. Germany also recently passed a law to increase the speed of its defense acquisitions.8

Similarly, earlier this year, the Lithuanian government approved a measure to expedite the government’s ability to purchase certain defense technologies (unmanned aerial vehicles, counter-drone systems, optical surveillance equipment, and laser target designators).

Further, because of their smaller defense budgets, European countries (and other international allies) are often more inclined than the U.S. government to adopt startup-built capabilities that provide cost-effective alternatives to traditionally expensive, exquisite systems. Countries with smaller defense budgets may actually have more demand for technology developed by early stage startups because they cannot afford more expensive systems. Many defense tech startups develop systems that match the capabilities of expensive, exquisite platforms at a much lower cost (ex: in Poland, exquisite F-35 fighter jet pilots have used $400,000 missiles to shoot down $35,000 Russian Shahed drones, a capability which could be achieved with a much cheaper system developed by a startup like Cambridge Aerospace).

For a customer like the U.S. DoD, cheaper systems developed by startups are more “nice to haves” rather than “need to haves,” as the U.S. military may already have exquisite systems that can fulfill a particular capability. Because of its large defense budget, the U.S. military is not as price sensitive as other countries (the U.S. military is willing to pay whatever it takes to achieve a particular capability), and as such, is already locked in to many more legacy exquisite systems with significant sunk costs that are difficult to replace with new, more cost effective technologies. For instance, in the case of commercial space, international militaries were often the earliest customers for American commercial space startups like Astranis, as they allowed other countries to access technology that provided capabilities that previously only the U.S. military had access to through exquisite systems.9

Startups also have the opportunity to fill capability gaps left by shortages of exquisite systems in Europe. European nations have underinvested in their weapons stockpiles for decades, and in recent months, European defense agencies have struggled to purchase more exquisite American defense systems altogether as the U.S. government has slow-rolled or blocked sales to European governments due to supply shortages. The current administration appears to be prioritizing replenishing American stockpiles of critical in-demand systems like the Patriot missiles (according to DoD officials, the U.S. only has about 25% of the missile interceptors it needs) by slowing or halting sales of those systems to international allies. Some European nations that have sent weapons to Ukraine are now struggling to re-fill their own weapons stockpiles, presenting another opportunity for startups to fill the gap.

Source: The Guardian

Startups with technologies that can provide similar capabilities to in-demand American exquisite systems have an opportunity to sell those capabilities to European nations while demand is high. Of course, startups may struggle to replicate all the features of the most exquisite systems, but they can target developing capabilities like attritable autonomous systems as well as low-cost air defense systems which can have asymmetric impact relative to their cost and manufacturability.

Beyond money and speed (European defense budgets are still only half the size of the U.S. defense budget) lies a deeper question: what does it mean to be a defense tech company in 2025 and yet remain absent from the most consequential confrontation between NATO and Russia since the alliance’s birth? Understandably, many American defense start-ups are focused on the Indo-Pacific theatre. However, proving their kit in Ukraine offers more than just a moral case: it provides a live demonstration that shapes perceptions in the Pentagon itself and allows them to sell to NATO countries in Europe with the “proven and used in Ukraine” seal of approval.

Operating in Europe also provides startups with the opportunity to actually test their systems on the battlefield in Ukraine in order to avoid mistakes made by past American defense tech startups. Modern and future warfare will be distinctly different from the wars of the past. Infamously, American drone companies have struggled to operate in Ukraine, as their design and testing was inadequate to operate in areas where electronic warfare was deployed.10 The only way to validate that new capabilities work is to test them on the battlefield. The Pentagon and all European militaries are watching Ukraine to understand what technologies will be needed in future conflict (in February 2025, NATO opened a center in Poland dedicated to analyzing lessons learned from the conflict in Ukraine) – by operating in Europe and Ukraine, startups can clearly demonstrate the importance of their technology, directly influencing future U.S. DoD procurement decisions. At the same time, many lessons learned in Ukraine will translate to a potential conflict in the Indo-Pacific, as Russia and China are collaborating closely on defense technology. Successfully operating in Ukraine will demonstrate to countries like Taiwan that technology is prepared to be deployed in an active modern war where it will face challenges like jamming and spoofing.

Already American defense tech startups have seen success partnering with European countries to deploy their technology in Ukraine. For instance, in February 2025 American FPV drone startup Neros won a contract from the International Drone Coalition, a Latvian and British government partnership, to deliver 6000 drones to Ukraine, enabling Neros to get direct feedback from Ukrainian warfighters to ensure their drones do not face the same fate as other American drone companies when faced with EW-denied environments. Just six months later, Neros won a $17M U.S. Marines contract for 8000 drones, showing the complementary nature of European and American defense contracts. Similarly, Anduril sold £30M worth of Altius 600m and Altius 700m loitering munitions for use in Ukraine through the International Fund for Ukraine, a £1.2B+ fund managed by the UK Ministry of Defense (MoD) with contributions from a number of European countries used to rapidly procure priority military equipment for Ukraine.

How can American startups penetrate the European defense market?

As with all startups, it is crucial for startups selling into European defense agencies to deeply understand their customers’ needs. While the U.S. and its European allies share many similar goals and adversaries, their tactical national security priorities differ. The U.S.’s national security priorities are primarily focused on 1) protecting the homeland from asymmetric threats (terrorism, organized crime, etc) and 2) preparing for a conflict against a peer adversary (China) in the Indo-Pacific.11 In contrast, Europe is preparing for a land war against an adversary (Russia) with imperial, expansionary ambitions. While many of the core technologies required for these conflicts may be similar, their application will differ when fighting asymmetric threats on the border vs. a war in the Indo-Pacific vs. a land war in Europe. For example, a hand-launched FPV drone may prove remarkably effective when fighting a land war from the trenches, but in an Indo-Pacific conflict, FPV drones, which can only fly 20 minutes or so before running out of power, would likely need to be launched from a mobile platform like a USV or aerial “mothership” in order to be effective given the tyranny of distance in the Indo-Pacific. So, when selling to the European defense market, startups must ensure that their systems are designed with European priorities in mind, and startups must be able to explain to European customers how their technology can be used in European theaters of war.

Because European defense ministries are focused on preparing for a future land war with Russia, they want technologies proven in Ukraine – potential European defense customers are sure to ask whether a startup’s product has been used there and how it performed. Startups must be ready with a clear narrative to answer those questions. For example, the Dutch Navy and Greek Army both publicly cited successful performance in Ukraine as a major factor in their decision to purchase V-BATs from Shield AI.

Startups should carefully choose which European customers to target. With 30+ countries in Europe, as well as hundreds of conferences and exercises, a small BD team that tries to cover all of Europe risks spreading itself too thin – without clear prioritization, efforts quickly become ineffective. Startups should prioritize working with countries with growing defense budgets who are dedicated to quickly acquiring the technologies necessary to respond to an immediate threat like Russia. Generally speaking, the further east you go in Europe, the quicker you’ll find customers willing to partner. European customers, particularly those in the east, are in desperate need of certain capabilities like air defense, so, presenting Eastern European procurement and government officials with a low cost, working product that can be manufactured at scale (preferably one that can be manufactured in Europe), will be met with open ears and a desire to move fast.

For instance, the Ukrainian Unmanned Systems Forces are particularly open and forward leaning and have already developed a system of support to help foreign companies test systems in Ukraine and field prototypes through initiatives like Brave 1. Savvy U.S. defense firms understand the value that comes from testing and collecting data in Ukraine – the validation, support, and references defense firms receive in Ukraine is priceless. Likewise, there is an emerging ecosystem of VC firms such as D3 with deep roots in Ukraine who are actively investing in US companies.

In addition to Ukraine, the Baltics (Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania) are a good place for startups to target for initial contracts. While their defense budgets are relatively small, due to their close proximity with Russia, the Baltics are highly motivated to quickly procure technologies needed to deter or stop a Russian invasion. Countries like Latvia also have specific funding programs, like the aforementioned International Drone Coalition, dedicated to fielding systems in Ukraine where they can get real battlefield testing.

Source: Atlantic Council

In the long run, though, defense tech startups cannot rely only on smaller countries like the Baltics to scale their European defense revenue. While these small countries are a good place to start to land initial funding and receive feedback from those close to the action, ultimately, American startups need to move on to countries with larger (and growing) budgets, particularly those which are actively reforming their procurement systems to improve efficiency. Some key targets include Poland and Germany. Poland has increased its defense spending from 2.7% of GDP in 2022 to 4.2% in 2024, with $48.7B in spending budgeted for 2025. Germany has increased its defense spending from 1.38% of GDP in 2022 to 2.4% in 2025 at $101B and plans to expand to 3.5% of GDP by 2029. Germany is also actively working to expedite its defense procurement processes for high impact systems. Germany’s waning car industry has made defense work in the country more appealing: specialist suppliers are looking for new markets, manufacturing facilities can be purchased at a discount, and highly skilled engineers have become easier to hire. Additionally, some NATO countries like Germany and Portugal have started to create more space for testing new capabilities such as drones. The German Bundeswehr has opened drone testing facilities at its “Innovation Lab” in Erding, and NATO hosts REPMUS, the world’s largest UXS exercise, in Portugal every September.

There are significant cultural and, often, language barriers between American startups and European defense officials. Sales tactics that work with American military units are unlikely to work with European units (ex: a hyper-aggressive sales culture that may work great when selling to the American Special Operations community may not land as well with French defense officials). American startups selling to European defense ministries should hire local European talent who speak the customer’s language to build and manage those relationships.

From first-hand experience inside a U.S. defense tech firm, the change in mood in Europe towards the U.S. this spring was striking. Regrettably, after Vice President J.D. Vance’s controversial speech at the Munich Security Conference in February 2025 and President Volodymyr Zelensky’s February visit to the White House, European ministries became noticeably cooler towards American interlocutors. Speaking English with an American accent often fuel scepticism in Europe; switching into German, in some instances, helped. Local hires do more than smooth relations with ministries of defense: they also open doors to domestic primes and start-ups, where pre-existing networks and understanding of the ecosystems shorten the path to partnership.

Often, U.S. defense tech companies attempt to expand into European markets with only minimal investment, typically hiring only a single U.K.-based BD representative to scout contracts across the continent before committing to larger teams or offices. While this approach can land a startup a few initial contracts, scaling across Europe will require a larger team with dedicated regional heads. Small sales teams tasked with closing deals across the entire continent can bridge the gap by working with a network of consultants and resellers with local expertise in individual countries’ markets. However, finding the right match and level of support for these local consultants can be time consuming, and many American companies tend to gravitate towards and compete for the same handful of standout consultants in each country. Similarly, on the PR and marketing side American startups may be able to scale their European footprint without meaningfully increasing headcount by working with local advisory firms for initiatives like government and public relations. For example, specialized advisories help defense firms navigate external relations in the U.K., while companies such as Darley have contract vehicles to support U.S. companies across other European territories.

A critical early decision for U.S. defense-tech firms is to delineate which subsystems of their platforms fall under ITAR (International Traffic in Arms Regulations). Typically, only particularly sensitive payloads, laser designators, or kinetic modules are ITAR-controlled. If export controls apply, the firm must navigate licensing through the Department of State (specifically the DDTC - Directorate of Defense Trade Controls, which is an office within the State Department’s Bureau of Political-Military Affairs) and, occasionally, the DoD. This process can typically be streamlined into a predictable ~60-day approval window when working with experienced export counsel. For more tightly regulated systems, sales may only proceed via the Foreign Military Sales (FMS) channel which is initiated by a Letter of Request to the U.S. Embassy / Office of Defense Cooperation and managed by DoD and State in concert under a government-to-government Letter of Offer and Acceptance framework. Generally the process is relatively straightforward, but startups should look to work with experienced export lawyers to move through the process smoothly and think about export early on, as European customers will certainly ask if a product is ITAR restricted.

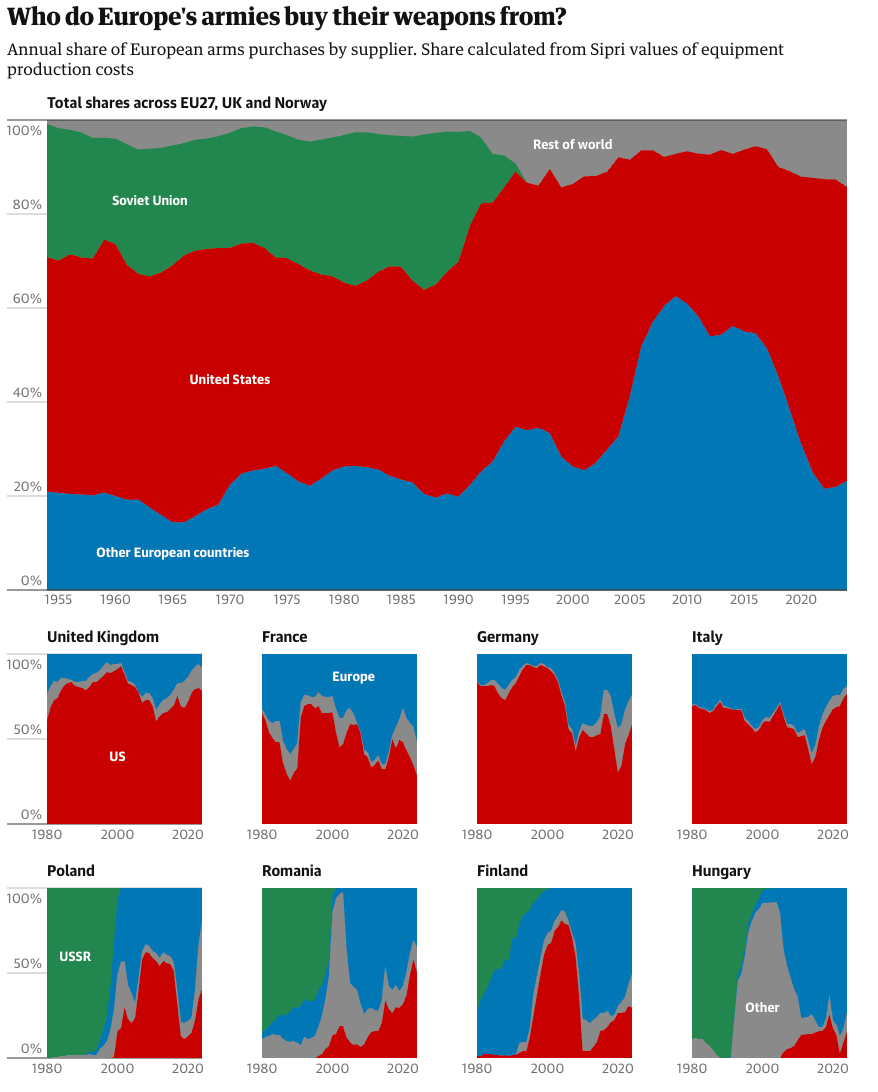

Given the current U.S. administration’s lean towards more isolationist foreign policy, many European governments are seeking to decrease the amount they spend on American defense products and increase spending on European companies. While today, the majority of defense systems procured by European NATO countries come from the U.S. (according to SIPRI, between 2020 and 2024 approximately 64% of the defense procurement of European NATO countries came from the US), this dominance of American defense firms in Europe is unlikely to persist indefinitely. In March 2024, the EU released its European Defence Industrial Strategy which stipulates that by 2030, at least 50% of member states’ procurement budget (and 60% by 2035) should go to EU-based suppliers, and at least 40% of defense equipment should be jointly procured. According to Politico, Germany’s new €80B rearmament plan only directs 8% of its budget towards American weapons systems (most of which will go towards procuring Patriot air defense missiles, torpedoes, AMRAMM missiles, ESSM missiles, and radio packages).

Source: The Guardian

Americans looking to sell defense systems to Europe will almost certainly be met with concerns around tech sovereignty. Many in Europe fear that an isolationist U.S. administration could restrict American companies from selling abroad if they are forced to prioritize supplying the U.S. in the event of a conflict. There are also fears within Europe that the administration could invoke a “kill switch” that would disable American military systems in Europe like the F-35 or cut off intelligence-sharing and military sales to the bloc (note that this “kill switch” theory is only a rumor; American firms like Lockheed Martin have denied the existence of any such kill switch). Further, European defense firms have launched aggressive lobbying campaigns to push governments to prioritize “buying European.” Previously, European governments were more open to purchasing systems from American defense startups in part because there were not many European defense startups with comparable capabilities (in fact, until recently, many European VC firms were prohibited from investing in defense). However, in recent years, many European (and recently also US) VC firms have shed those restrictions and funded a new generation European defense tech companies like Quantum Systems, STARK, Swarmer, Intellic, Comand AI, Helsing, and Cambridge Aerospace. The rise of this robust European defense tech ecosystem – offering European governments more domestic cutting-edge options than ever before – coupled with a more isolationist U.S. administration, has made it increasingly difficult for American startups without European ties to compete in the region.

Source: Dealroom State of Defence Tech 2025

European buyers want to have confidence that they will be able to access defense systems during a crisis, and so they will prioritize working with European companies or American companies with European manufacturing facilities or partnerships. As such, it will be crucial for American defense startups to proactively work to build trust with European countries they wish to do business with by 1) establishing partnerships with European defense companies with pre-existing trusted relationships with European defense ministries and 2) actively investing in Europe by opening offices and manufacturing facilities on the continent as well as building up supply chains that focus on European-made products.

American defense primes have run this playbook for years. For instance, RTX is partnering with Norwegian defense company Kongsberg on NASAMS air defense systems and with European multinational defense corporation MBDA to produce the GEM-T interceptor for the Patriot air-defense system. Similarly, Honeywell recently acquired Italian defense firm Civitanavi Systems to reach the Italian market, and Kratos Defense announced a partnership with the European aerospace giant Airbus to deliver a customized version of Kratos’s XQ-58A Valkyrie CCA to the German Air Force (Luftwaffe), equipped with Airbus’s mission system.

American startups are starting to follow suit. In June 2025 Anduril announced a partnership with Rheinmetall, Germany’s largest defense company, “to co-develop and deliver a suite of software-defined autonomous air systems and advanced propulsion capabilities for Europe.” Anduril’s press release emphasizes that the partnership reflects a “built with, not for” philosophy, prioritizing local control, transparency, and adaptability over dependency or vendor lock-in. Anduril is clearly aiming to reassure its European customers that working with the company will not make them reliant on a U.S. firm that could one day withdraw support, and aiming to deliver ITAR-free versions of their products to the German Bundeswehr.

Similarly, American space startup Loft Orbital recently announced a partnership with European defense startup Helsing to jointly develop and deploy a multi-sensor satellite constellation that “will harness AI-driven capabilities to deliver real-time intelligence and situational awareness to European defense and security stakeholders.” British defense company BAE Systems has also partnered with American startup Red6 to deploy augmented reality (AR) on Hawk TMk2 aircraft with the British Air Force. In May, U.S. drone company Red Cat Holdings announced its plans to partner with a leading Ukrainian manufacturer of USVs (likely Ukrainian MAGURA V7 USVs, the first USVs to down fixed-wing aircraft, shooting two Russian Su-30 fighters out of the sky over the Black Sea with surface-launched AIM-9 Sidewinder missiles) to develop its own USVs under its new “Blue Ops” division.

In addition to partnering with European companies, European governments also want to see American defense companies actively investing in Europe in order to bolster European strategic sovereignty. Several American defense startups have opened European offices and launched European subsidiaries in a bid to win more European business. In April, American maritime autonomy startup Saildrone established a European subsidiary and opened its European headquarters in Copenhagen after closing a $60M funding round led by EIFO, Denmark’s sovereign wealth fund. Since opening its Danish office, Saildrone has deployed several systems in the Baltic Sea with the Danish military to protect undersea infrastructure like cables and pipelines from Russian threats. In May, American autonomous systems startup Applied Intuition opened an office in the U.K. and established a London-based subsidiary backed by £50M in foreign direct investment. According to the press release, this initiative is “aimed at building sovereign capability and creating high-value jobs in engineering and research and development” in Europe. In September, Shield AI announced its plans to open an Oslo office in order to build on its partnerships with Norwegian defense firms Radionor Communications AS, Teleplan Globe, and Ubiq Aerospace. Anduril has long had a U.K. subsidiary and U.K. office – Anduril established its U.K. subsidiary in 2019, just two years after it was founded, and opened a U.K. office shortly thereafter. In March, Anduril announced that they were considering opening a drone factory in the U.K. to continue expanding its investment footprint in the country.12

Conclusion

Selling into European defense markets is not easy, but it is likely to be increasingly impactful: both for a startup’s bottom line as well as for the defense of Western democracy against authoritarianism. As Moscow becomes increasingly aggressive, the opportunity in Europe is too pressing for American startups and VCs to ignore.

In the past, closing defense deals in Europe often dragged on for years. Today, Russia’s war and Europe’s decades of underinvestment in credible deterrence have flipped the equation. Governments are now eager to procure proven, off-the-shelf systems in a matter of weeks.

Winning in this environment requires urgency in the form of delivering solutions into Ukraine for operational testing, or, at the very least, staging live demonstrations across Europe on short notice. Lead times must be measured in weeks or months, not years, and firms must be able to iterate quickly as Russia is now doing in adapting its own systems.

Longer term, credibility depends on more than fast delivery. Building local supply chains, establishing production and MRO facilities, working with local SMEs and primes, hiring nationals to navigate procurement, and deploying skilled field engineers to manage training and roll-outs will be essential to secure sustained trust and contracts.

Selling into European defense markets is no longer a distant opportunity: it is an immediate, high-stakes challenge. For American defense startups willing to commit resources, navigate local cultures, and think long-term, Europe offers a chance to grow their business while contributing directly to the security of Western democracies at a critical moment in history.

For those looking to learn more about the European defense market, we have included a list of resources below:

A few ideas for events to attend in Europe:

Berlin Sicherheitspolitische Tage – Focused on German national security and policy

Munich Security Conference – Hosted every year in Munich, similar to Reagan National Defense Forum

Globsec – In Prague, focussed on CEE policy questions including defense

Eurosatory – Hosted every two years in Paris

NavyTech – Hosted every year at a different location each year, next event is in Sweden

ILA Berlin – Hosted every two years in Berlin, their Paris Air Show, focused on air domain

MSPO Poland – Hosted every year in Kielce

A few ideas for European VCs who are investing in defense:

201 Ventures – GP Eric Slesinger invested in CX2, Delian, Isembard

Air Street Capital – Single GP Nathan Benaich, invests in AI-first companies

Alpine Space Ventures – Munich based, space focused firm founded by SpaceX alum

Atlantic Labs – Pre-seed only, deep tech focus

Balderton – Led Series C in Quantum Systems

D3 – Early stage Ukraine focus

Darkstar – Early stage Estonia/Ukraine focus

Lakestar – Invested in Auterion, Varda, Helsing, and Isar Aerospace

Plural – UK-based VC invested in Helsing and Labrys

Presto Ventures – Prague based, recent partnership with CSG to invest in Firestorm

Project A – Invested in ARX robotics and Quantum Systems

A few ideas for news sources on European Defense Tech:

European Security and Defence – Journal covering European security and defense policy

IISS – Provides authoritative analysis on European security and strategic affairs, insights on regional threat perceptions - also host events

RUSI – The world’s oldest defense and security think tank, based in London, also hosts events

Sifted – Covers Europe’s startup and venture landscape, including the emerging defense-tech ecosystem

Tectonic – US defense tech focus with relevant pieces on Europe too, hosting an event in Paris this November

Tech.eu – All about European startups

EU = European Union

NATO = North Atlantic Treaty Organization

From @Gerashchenko_en, who also lists incursions from the past weeks: In Poland, on August 20 a Russian drone exploded over Lublin Voivodeship. On September 10 nineteen Russian drones entered Polish airspace. In Norway, drones were sighted on April 25 northeast of Vardø, on July 24 in eastern Finnmark, on August 18 northeast of Vardø, and on September 22 over Gardermoen. In Latvia, on September 18 a drone tail part was found on a beach. On September 25 five Russian aircraft approached Latvian airspace and Hungarian jets took over. In Estonia, on September 19 a Russian MiG-31 spent twelve minutes in Estonian airspace. In Romania, on September 13 a Russian drone entered Romanian airspace and was tracked by two F-16s. In Germany, on September 26 several drones were seen over Schleswig-Holstein. In Denmark, on September 22 Copenhagen airport was closed due to drones. On September 25 Aalborg and Billund airports were closed, with drones sighted at Esbjerg, Sønderborg and Skrydstrup. On September 26 Aalborg airport airspace was closed again. In Sweden, on September 26 drones were spotted near Karlskrona Naval Base. In Lithuania, on September 26 Vilnius airport was closed twice after drone sightings. In Finland, on September 27 a drone over Rovaniemi power plant was reported, though the incident occurred earlier.

NATO Article 4 is a provision in the North Atlantic Treaty that enables any member country to call for consultations with other NATO members whenever it perceives a threat to its territorial integrity, political independence, or security. Unlike Article 5, which deals with collective defense in the event of an armed attack, Article 4 is about dialogue and coordination. Essentially, it’s a formal mechanism for allies to discuss concerns and assess potential responses before a crisis escalates. This article is often invoked in situations of heightened tension or emerging threats, serving as an early-warning and diplomatic tool within the alliance.

FPV = First Person View

DHS = Department of Homeland Security

BAAINBw = Bundeswehr Equipment, Information Technology, and In-Support Service

Which has been challenged again in court recently by the Budget Committee

For instance, consider remote sensing: the U.S. military has spent decades launching exquisite satellites capable of high resolution earth observation across a number of sensor modalities (RF, cameras, EO/IR, and more). Thus, the U.S. military moved slowly to adopt commercial remote sensing technology because it already had access to remote sensing capabilities through its exquisite systems. In contrast, many smaller European, Asian, and Middle Eastern allies have not had the funds to launch their own satellites and as a result do not have their own remote sensing capabilities. So, many of these countries have been more willing to work with early stage startups capable of providing remote sensing at a much cheaper price point. For example, Planet Labs, an earth observation satellite company, receives more than half of its revenue from international customers (in fact, Planet Labs’ largest ever contract is with a Japanese customer, even though the Japanese defense budget is much smaller than the U.S.). Similarly, much of space communication startup Astranis’s early customer revenue came from countries like Taiwan (with whom they signed a $115M contract), Thailand, Mexico, the Philippines, and others, rather than the U.S.

For more on what it takes to operate cutting edge technology in EW-denied environments, see my previous blog posts on the subject: Winning 2027 Starts Now; Manufacturing for the Mission; Field or Fail: Building the Attritable Arsenal of Democracy.

For more on the kind of technologies the U.S. will need to fight a war in the Indo-Pacific, see my previous post “Winning 2027 Starts Now.”

While the U.K. can be a good landing spot for American startups given cultural and linguistic similarities with the U.S., it is important not to overindex on the UK purely for it being English-speaking and part of AUKUS. The U.K. system is more complex than many other European countries’ systems, and it can take years to win meaningful contracts (one exception being the UK donations to Ukraine managed through Taskforce Kindred and the UK-led International Fund for Ukraine (IFU)). The MOD’s Defence Equipment & Support (DE&S) processes are often times gradual, rules-heavy, and tailored to large primes who have decades-long relationships, lobbying networks, and political capital in Whitehall (BAE Systems, Rolls-Royce, MBDA, Thales UK to name a few), not agile foreign entrants.

These have been extremely helpful as a Dual-Use Founder looking at growth, thank you!

France tends to put most of its procurement money into domestic companies, while Germany, by contrast, has until recently directed a larger share of its spending toward external suppliers rather than its own industry. https://thebigbyte.substack.com/p/european-defence-tech