Field or Fail: Building the Attritable Arsenal of Democracy

What it will take for DoD to procure and field FPV and other attritable drones at scale

FPV1 and other attritable drones have proven to be an integral part of modern conflict. When the war in Ukraine began, artillery caused 60-80% of casualties, as it has in every war since WWI, but now drones and other uncrewed systems have emerged as the new, most lethal capability on the battlefield, with FPV drones responsible for an estimated 60-80% of casualties.

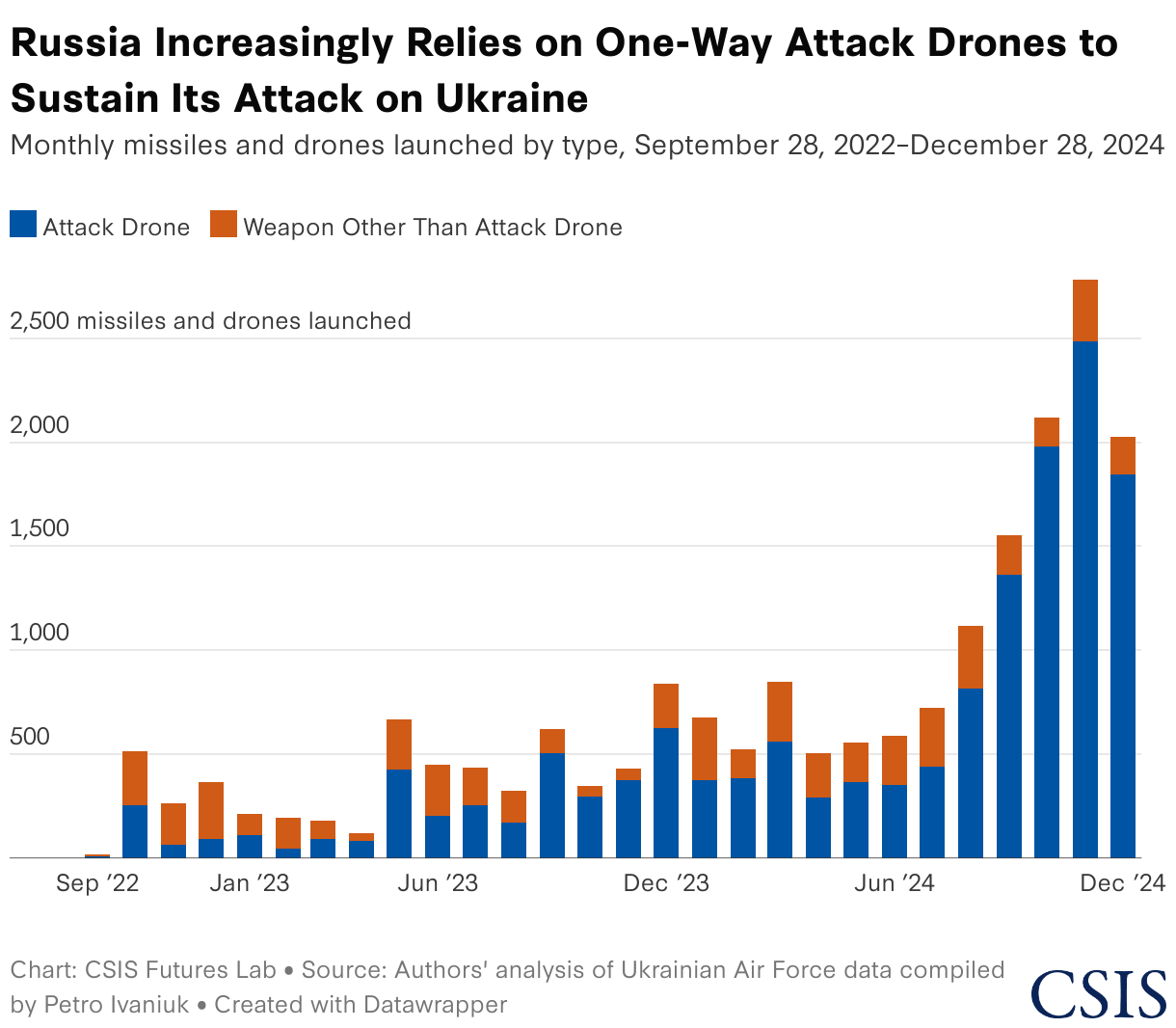

Despite FPV drones’ clear importance on the modern battlefield, the U.S. Department of Defense (DoD) is not on track to procure and field FPV or other drones at scale, and our current industrial policy shows no intention of changing that. The DoD has yet to fully recognize drones as strategic combat assets, failing to align budget priorities, industrial base planning, and Concepts of Operations (CONOPS) with their growing importance on the modern battlefield. The challenges outlined in this piece are symptoms of this strategic oversight, an approach starkly contrasted by Ukraine and Russia, which have both rapidly adapted to integrate drones at every level of warfare, each procuring millions of drones a year. China, the world’s largest producer of low-cost drones, undoubtedly recognizes the strategic importance of attritable systems as well.

A number of barriers stand in the way of fielding these systems within the U.S. DoD including lack of sufficient budget, arduous cybersecurity and hardware certification processes, lack of realistic testing infrastructure, at-risk drone component supply chains due to overreliance on Chinese suppliers,2 and strict pilot training requirements. While there are organizations within DoD, such as the Defense Innovation Unit (DIU), working to expedite procurement of attritable drones, far more systemic change is needed to ensure the US remains competitive in future conflicts.

Last month, I published a piece with Gleb Shevchuk, an engineer at Neros, detailing Neros’s path to becoming the first FPV drone manufacturer to join the DIU’s Blue UAS list (a milestone that has since been followed by the addition of one more FPV drone model). This month, I’m joined by Trent Emeneker, a program manager at DIU who leads the Blue UAS initiative, to share the story from the government’s point of view and discuss what the Department needs to do to field FPV drones at scale. In particular, we argue that the DoD needs to establish a joint, central authority responsible for establishing cohesive policy and guidance across the enterprise relating to attritable UASs and for large-scale attritable UAS drone procurement.

A bit of background for those who didn’t get the chance to read last month’s piece: DIU is an organization within the DoD focused on accelerating the adoption of commercial technology to solve operational military challenges at speed and scale. DIU manages the Blue UAS list, a list of vetted commercial drone platforms that are both NDAA compliant and meet the DoD’s cybersecurity standards. Designed to accelerate the adoption of secure, reliable small unmanned aerial systems, drones on the Blue UAS list bypass the need for a DoD exception to policy (ETP) because they’ve completed cybersecurity evaluations, met NDAA compliance supply chain standards, and received all required administrative documentation. A core objective of the Blue UAS program has always been to strengthen the domestic and allied drone industrial base, ensuring that U.S. and allied militaries are not reliant on Chinese-made drones.

It is not easy for a company to get on the Blue UAS list, with entry possible via one of two routes: 1) A DoD Service or Program Office can sponsor a platform for direct entry, or 2) a manufacturer can go through DIU’s competitive entry process

Drones on the Blue UAS list go through a stringent cybersecurity evaluation and must not include the following critical components if they are manufactured in China, Russia, Iran, or North Korea: flight controllers, radio communication systems, data transmission devices, cameras, gimbals, ground control systems, operating software, network connectivity, and data storage. Today, China builds 80-90% of all consumer drones globally, and controls 90% or more of the related global supply chain. Notably, China dominates close to 100% of manufacturing of several key drone components such as batteries, motors, and magnets.

Bringing the First FPV Drone onto the Blue UAS List

Based on consistent feedback from warfighters and lessons drawn from recent conflicts, including those in Nagorno-Karabakh, Ukraine, Syria, and Gaza, DIU recognized a clear and urgent need within the DoD for kinetic FPV drones. However, before Neros, there were no FPV drones on the Blue UAS list, making it impossible for warfighters to procure NDAA compliant FPVs. So, DIU set out to partner with one of the DoD services to identify an FPV drone for the Blue UAS list. DIU sought out potential partners in the Army and the Marine Corps, and ultimately found a small but agile team at the Marine Corps Warfighting Lab (MCWL).

Before Neros joined the Blue UAS list, all approved UASs on the list cost at least $10k (and some an order of magnitude more) – an unsustainable price point in a world where the lifespan of a drone in combat ranges from minutes to days. DIU supplied a range of vendors as options for MCWL to consider to add to the Blue UAS list, and MCWL narrowed the list down to three potential solutions. From there, DIU and MCWL consistently engaged with those companies to drive their timeline to build an NDAA compliant platform, providing feedback on development, analyzing components to rapidly assess NDAA compliance, and connecting firms directly to the warfighter for end user feedback. Ultimately, the Neros Archer platform was competitively selected at the Blue UAS Refresh, and MCWL chose Archer as a sponsored platform.

The Blue UAS certification process includes both a supply chain review as well as a cybersecurity review. As part of the supply chain review, a team of third party experts contracted by DIU physically takes apart drones and runs forensic analysis on each component, examining part markings and serial numbers, to verify manufacturing origin and ensure NDAA compliance. DIU also analyzes the ownership structures of companies on the Blue UAS list to ensure they do not have significant ties to adversary nations.

Drones on the Blue UAS list are required to have an Authority-to-Operate (ATO). The ATO process is notoriously expensive and time consuming, but service components can sponsor companies for an ATO sponsored by DIU.

Part of the value of Blue UAS is that most (but not all) Services accept a Blue UAS ATO, so Blue UAS vendors do not need to repeat the ATO process for different services (for more on the intricacies of ATO reciprocity policy, see footnote3). In this case, the MCWL sponsored Neros and provided the required funds for them to get their ATO. The process from initial conversation at MCWL to published ATO took only 10 months, an extremely rapid pace by any measure, especially considering the limited budget, requirement to develop and source new NDAA compliant parts, and in reference to a standard program of record which would stretch to closer to 10 years than 10 months.

Challenges to Procuring and Fielding FPV Drones

Blue UAS certification is only the first step to actually fielding any type of drone at scale. A number of other barriers to adoption exist including limited funding, lack of realistic testing facilities, and burdensome training requirements. Some limited progress has been made to ease these challenges, but there is still much more that must be done.

Funding

First and foremost, there is limited funding available for DoD units to actually procure and maintain FPV drones, as there is no formal program funding FPV drones. The funding set aside thus far for attritable systems is far from sufficient to field these systems at the scale needed to make a real difference. According to analysis by AUVSI,4 the 2025 DoD budget has just $350M for tactical level UAS systems. With this funding, DoD is only expecting to field about 4000 UASs, bringing the average cost per system close to $100k. For reference, some drone factories in Ukraine can produce more than 4000 drones per day. The Ukrainian military receives more than 200,000 FPV drones per month and plans to ramp up domestic production to 4,500,000 FPV drones per year by the end of 2025, each of which costs just a few hundred dollars.

Historically, the DoD has not considered costs strategically when deciding to adopt new technologies. However, in the age of drone warfare, costs will be a key determinant of success. DoD must prioritize the ability to field mass quantities of systems affordably, signaling a shift where cost per unit will play a far more critical role than in the past, when large, high-priced defense platforms were the norm. As Army Secretary Daniel Driscoll said during a War on the Rocks interview, “Russia has manufactured 1 million drones in the last 12 months, that just makes us have to rethink the cost of what we're buying…We are the wealthiest nation, perhaps in the history of the world, but even we can’t sustain a couple-million-dollar piece of equipment that can be taken out with an $800 drone and munition.”

To further drive home the point, consider the recent Red Sea conflict with the Houthis: the Navy deployed a multi-billion-dollar carrier task force to the region, which quickly became a target for low-cost Houthi drones. To counter them, the Navy fired over 70 SM-2 missiles, spending $140 million to destroy just $2 million worth of drones. The economics of the current exquisite U.S. force simply do not work.

The funding challenge was eased slightly in February 2025 when OUSD A&S5 released a memo authorizing servicemembers to purchase Blue UAS approved drones with government credit cards. Leaders within DoD can now use their own discretion to buy Blue UAS approved drones to experiment without a formal contract or program, saving significant time and paperwork. However, this memo still does not do much to move the needle to actually fielding these systems at scale because units were not given any funding to actually buy platforms. Having the authority to do something is great, but if there’s no money to actually do it, then the authority isn’t worth very much.

The Army is working on an FPV drone program of record (POR) called the Purpose Built Attritable System (PBAS) program. However, based on the Army’s historical timelines for UAS development, deployment of drones from this program is likely multiple years, potentially close to a decade, out from initial fielding. For example, in early May, the Army canceled the FTUAS project, which selected its initial prototypes in 2019, but 6 years later was not close to actually fielding platforms to soldiers. The Army has already spent several years writing requirements for the PBAS program. Assuming funding is available immediately (usually, receiving a budget through the POM cycle takes at least 3 years) it will take several years of prototyping and testing before a final vendor is selected. As another example, the Army finished Tranche 2 evaluation for its Short Range Reconnaissance project (requirements for which were completed in 2013) in November 2024, took another six months to decide on the winner, and now six months later, the first platforms selected were just delivered. Unless something changes drastically, the DoD is likely still 5-10 years away from fielding FPV drones at scale through the traditional acquisitions process.

Army’s Short Range Reconnaissance Project Timeline

Testing and Certification

Another challenge facing FPV drone deployment is the lack of realistic testing infrastructure. It takes months to reserve a slot at a DoD drone testing range, and the sites that are available are expensive and lack the ability to replicate a fully contested electromagnetic spectrum. This lack of realistic testing infrastructure is not a technical challenge (EW jammers are cheap and easy to order online), rather it is a regulatory and policy challenge. In fact, it is prohibited to realistically test FPV drones even at DoD-run testing facilities. As I’ve written about previously, as the war in Ukraine showed, we cannot rely on access to GPS, resilient communications, or any other capabilities that rely on spectrum dominance. American drone companies have struggled to operate in realistic electronic warfare (EW) conditions, in part due to lack of testing infrastructure.

There are four major positioning satellite constellations: GPS (US), Baidu (China), Galileo (EU), and GLONASS (Russia). While at DoD drone testing ranges, operators are usually only allowed to jam GPS, the American positioning satellite constellation. However, many drones are able to receive positioning data from multiple satellite constellations.

Further, when drone operators want to test jamming a part of the spectrum used for communication, they are required to get approval to jam specific frequencies. However, in general it is not possible to jam all frequencies that a drone may be able to broadcast across in a testing environment. There are several frequency bands such as GPS L-1 that are federally protected and may never be jammed during testing (but will almost certainly be jammed during a conflict).

In addition to the Blue UAS list requirements, drones must go through several other certification processes before being used by the DoD. Drones using custom radios must go through the months- (and sometimes years-) long J/F-12 process to get NTIA6 approval. While some radios are already pre-NTIA approved, most drones for DoD applications use custom radios which are more EW-resilient. Drones are also required to get an airworthiness certification (each service has their own airworthiness certification process7), which includes an onerous battery certification process for the Department of the Navy that can take more than 12 months.

Some program certification requirements for unmanned systems simply make no sense at all. For example, a recent Service POR for a three pound unmanned quadcopter, during the prototyping phase, included a requirement to brief egress procedures. In manned aviation, egress procedures cover how a pilot leaves the aircraft in case of emergency. While egress procedures are clearly not applicable to uncrewed systems in general, much less a three pound drone, the existing DoD acquisitions bureaucracy replicates what it has always done.

Training

Until recently, the DoD had arduous training requirements for those looking to become drone pilots. All UAS operators were required to go through a flight physical, as if they were airplane pilots, and had to attend months of training (traditional remotely piloted aircraft training for systems like MQ-9 Reapers takes about a year). In August 2024, the USMC released a MARADMIN loosening the training requirements for UAS operators, stating that Blue UAS Group 1 operators are not required to train at a formal learning center. Instead, to qualify as a Blue UAS Group 1 operator, Marines just need to complete a two week online course and undergo training provided by the drone manufacturer. Note that currently there is no formal FPV drone training within DoD outside of a single school run by Special Operations Command (SOCOM) that trains just a handful of operators each year (almost all of whom are special forces).

Recommendations for Accelerating the Pace of FPV Drone Adoption

While progress has been made to field more FPV drones within the DoD, it is clear that much more needs to be done in order to prepare for future conflicts and ensure credible deterrence. Fundamentally, the DoD still treats FPV drones like aircraft when they should be treated more like ammunition.

Today, no single organization within the DoD has clear authority to establish department-wide policy or guidance for UAS and FPV drone training, testing, and procurement. The Army’s PEO Soldier and PEO Aviation both have some responsibility for drones, as does the Navy’s PMA 263, Army Applications Lab, and Special Operations Command (SOCOM). As such, each organization within DoD sets drone policies in a piecemeal fashion.

The DoD needs to establish a central authority responsible for large-scale attritable UAS drone procurement and for establishing cohesive policy and guidance across the enterprise. This organization should be a joint program executive office (JPEO), modeled off an organization like JPEO Armaments & Ammunition (which is responsible for development, procurement and fielding of lethal armaments and ammunition). This joint organization should have a substantial budget – in the range of $10B8 each year – to procure, deliver, and develop UAS platforms of all shapes and sizes, from FPVs to ISR to one way attack to cargo, and all related capabilities.

Rather than draft detailed and rigid requirements, this new organization should focus on fielding a capability of record that meets warfighter end user needs. The DoD should not try to squeeze all possible requirements into one system. In fact, DoD should not try to write rigid requirements for FPV drones at all, focusing on capability, which is best described as something that can meet the needs for warfighters and their problem sets. Instead of requirements, this capability of record can field systems from several different vendors with different kinds of payloads, each with slightly different capabilities depending on specific mission sets. For instance, rather than specifying that a drone needs to have a camera with particular specs, a capability of record would specify that a drone needs to have the capability to detect a target (ex: a tank) within a certain distance. Any kind of camera that meets this capability would be eligible.

Additionally, testing, training, and compliance policies must also be fundamentally reimagined. Why are FPV drones required to go through the same cybersecurity and hardening certification procedures as multimillion dollar systems? Why does it matter if an FPV drone is perfectly water resistant or dust proof? Many FPV drones are made to be used once!

This organization should set up new, expedited pathways for FPV drones to achieve cybersecurity and spectrum certifications and should draft new hardening standards that recognize the attritable nature of these systems, optimizing for cost, ease of use, and speed of deployment rather than infallibility. Certifying new attritable drone radios and batteries should not take up to 18 months, especially given the need for continual redesign and recertification in response to the rapidly evolving EW environment. Getting cybersecurity certifications for FPV drones should not require hundreds of thousands of dollars or take nearly a year to complete. Attritable drones should not be required to meet the same hardening standards as multi million dollar aircraft, and FPV drone pilots should not be required to go through months of training and a full physical exam to fly FPV drones. This organization should develop new, expedited training programs specifically designed for those learning to fly cheap, attritable FPV drones.

To support experimentation and development, the proposed joint authority should prioritize providing attritable drone developers with access to realistic EW testing environments. One approach is to establish dedicated government-run drone testing facilities tailored for realistic EW scenarios. Alternatively, the DoD could relax existing restrictions to enable drone developers to conduct EW scenario testing at current DoD ranges, or this new organization could make it easier to test systems outside of DoD run testing facilities, within reason. In the short term, as new testing facilities are being stood up, this organization should also help FPV drone manufacturers access international testing facilities, like those in Ukraine, in order to ensure American FPV drones are able to compete against a peer adversary.

Finally, domestic and allied component supply chains must be strengthened to reduce dependency on adversary-controlled materials and components. Today, most FPV drones remain highly dependent on Chinese components and materials. While drones on the Blue UAS list like Neros Archer have found non-Chinese alternatives for some components, even NDAA-compliant drones still tend to rely on Chinese suppliers for components like motors, magnets, batteries, and carbon fiber. This new organization should actively support the US and allied FPV drone industry by investing in onshoring, near-shoring, and / or friend-shoring FPV drone component manufacturing, with special focus on motors, magnets, batteries, and carbon fiber.

Conclusion

The story of Neros’s rapid certification onto the Blue UAS list is a promising example of what’s possible when government and industry work together with urgency and purpose. But if the DoD is serious about fielding attritable drones at the scale needed to deter and win future conflicts, it must move beyond one-off successes. That means rethinking legacy acquisition frameworks, dramatically simplifying compliance requirements, standing up realistic testing infrastructure, and treating attritable drones not as exquisite aircraft but as scalable, disposable tools of modern warfare, akin to ammunition. The conflicts unfolding around the world have already shown us what’s at stake. With Russia’s recent combat experience and China’s drone manufacturing prowess, our adversaries have the upper hand in producing and deploying drones at scale. The U.S. military will be at a severe disadvantage if forced to fight against mass quantities of low-cost drones, just as the Navy has been at a disadvantage in defending its ships against low-cost Houthi drones. Now, the United States must translate those battlefield lessons into institutional reform, before the next fight arrives.

As always, please reach out if you or anyone you know is building at the intersection of national security and commercial technologies. And please reach out if you want to further discuss the ideas expressed in this piece or the world of NatSec + tech + startups. Please let us know your thoughts! We know this is a quickly changing space as conflicts, policies, and technologies evolve.

FPV = First Person View. FPV drones are small, cheap, remote-operated copter-powered UASs.

For more on China’s central importance to drone supply chains, see “Silicon Valley’s Military Drone Companies Have A Serious ‘Made In China’ Problem.”

While the Resolving Risk Management Framework and Cybersecurity Reciprocity Issues Policy memo from May 2024 directs that Services should grant reciprocity to ATOs from other Services (meaning, for example, that an ATO provided by the Air Force would also be accepted by the Navy) it is not mandatory. Without ATO reciprocity, vendors are required to repeat the ATO process for each new DoD customer they wish to sell to.

For full context, the Cybersecurity Reciprocity Playbook outlines that “To improve the use of reciprocity, CIO has emphasized in policy the ‘re-use’ of security testing evidence as the foundation for reciprocity, eliminating and invalidating the practice to issue an authorization decision memo without examining the body of evidence. DoDI 8510.01 states, ‘The DoD Information Enterprise will use cybersecurity reciprocity to reduce redundant testing, assessing, documenting, and the associated costs in time and resources.’ By focusing on ‘re-use,’ CIO ensures data is provided to Components to enable risk-based decision making, while eliminating duplication of effort….Reciprocity is not a passive acceptance of security assessments, certifications, or authorizations from other entities without careful consideration, and comprehensive review of the context, risk factors, sensitivity of the data, and relevance to the specific systems or networks within its purview. Instead, reciprocity involves a thoughtful, risk-based assessment process and a careful examination of the BoE to determine their applicability and suitability within a specific security landscape.”

Note that we have seen no evidence that Services are in fact adopting reciprocity to accelerate ATO adoption. In fact, the USAF recently required that all UAS platforms have controls implemented for 720 of possible controls, rather than only implementing controls for the things that actually apply and the implementing memo specifies that no control may be marked “Not Applicable”. The Army requires that 473 controls be implemented. When DIU examines platforms, we use about 50 possible controls because those are the ones relevant to a UAS. Multiple Services have asked DIU to provide ATOs for platforms that either already have an ATO through another Service, or are a Program of Record (POR) for another Service. While they will accept a Blue UAS ATO, which is a step in the right direction, DIU does not want to be, and should not be, the required middle man to establish reciprocal ATOs.

AUVSI = Association for Uncrewed Vehicle Systems International. AUVSI is the world’s largest nonprofit organization dedicated to the advancement of uncrewed systems and robotics.

OUSD A&S = Office of the Undersecretary for Defense for Acquisition & Sustainment

NTIA = National Telecommunications and Information Administration

For more on the airworthiness certification process, see for example page 8 of this document which shows the complicated process required to get airworthiness certification in the Army.

This number is based on an annual procurement target of approximately 2 million drones, with a weighted average unit cost of around $5,000. The vast majority (roughly 98%) would be low-cost FPV and ISR systems, complemented by a small number of more expensive long range one way attack (LROWA) and advanced ISR platforms.

Note: The opinions and views expressed in this article are solely our own and do not reflect the views, policies, or position of our employers or any other organization or individual with which we are affiliated.

Maggie and Trent, great article. We wrote about a similar topic last week except used Skydio as our company of reference. We end up taking the counter position.

supply chain resilience is extremely important but relevance of FPV in a cross straits scenario? Potentially less impactful than land based war fare as distances and defense are much different.