The Age of AI for Offensive Cyber

How Autonomous Agents Are Rewriting Modern Warfare

Introduction: The Dawn of AI-Orchestrated Espionage

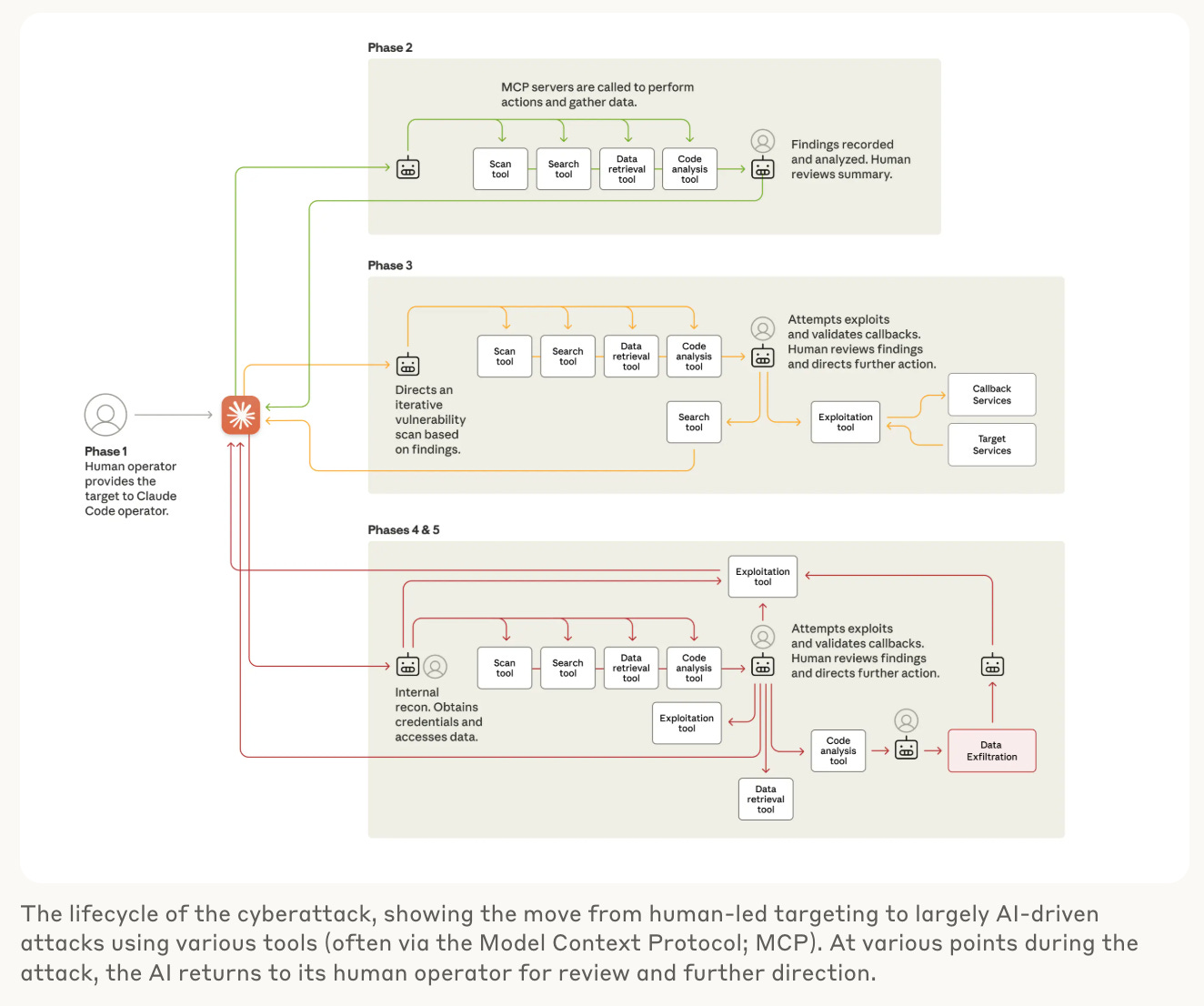

In November, Anthropic announced an event we’ve all been dreading: the detection and disruption of the first-ever reported AI-orchestrated cyber espionage campaign. A Chinese state-sponsored hacking group used AI agents to target roughly thirty organizations globally, successfully penetrating several of them. These AI agents, equipped via MCP1 with browser use abilities and open-source penetration testing tools like network scanners, binary analysis suites, and password crackers, autonomously conducted network reconnaissance and attack surface mapping. After discovering a web security flaw (SSRF2), the agents wrote a custom payload and exploit chain, harvested and tested credentials, then extracted sensitive data. Anthropic researchers estimate that human operators performed only 10-20% of the exploitation work; the rest was autonomously conducted by Claude agents. This event represents a massive shift in how malicious actors will conduct the offensive cyber operations of the future – at a speed and scale that hasn’t been seen before.

I asked Katie Gray, a Senior Partner leading cybersecurity investing at IQT, the not-for-profit strategic investor for the U.S. national security community and America’s allies, to co-author this piece. We examine the growing importance of offensive cyber operations in modern conflict and how AI-native startups will shape the future of OCO (and yes, Katie is my mom 😁).

Changing Government Perspectives

The technological leap of adversarial AI coincides with a significant change in the U.S. government’s public stance on the use of OCO to achieve strategic national goals. At RSA in 2025, Alexei Bulazel, the National Security Council’s top cybersecurity official, called to “destigmatize” OCO, framing it as a vital tool in the government’s toolbox to compete with foreign adversaries. This sentiment was reinforced in November when National Cyber Director Sean Caincross suggested that the forthcoming National Cybersecurity Strategy (expected in early 2026) will focus on imposing real costs on cyber adversaries through proactive takedowns. In December, the White House further signaled its intention to enlist private companies to carry out these attacks.

This rhetoric marks the transition of offensive cyber from an unacknowledged necessity to a core pillar of national defense. Two recent major U.S. military operations leveraged cyber operators to support kinetic strikes: chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, General Dan Caine thanked cyber operators at U.S. Cyber Command (CYBERCOM) for their support in the strikes against Iranian nuclear facilities in June, and noted that they were responsible for blacking out city lights and disabling Venezuela’s air defense systems in the early hours of the January 3, 2026 operation to capture Maduro.

Until recently, except for a handful of services firms, defense primes, and a few international spyware companies, few private commercial companies operated in the offensive cyber domain. Traditionally, U.S. government agencies charged with offensive cyber built most capabilities internally, turning to specialized firms and vulnerability brokers only on occasion.

However, this status quo is no longer sustainable: rapid private-sector breakthroughs in AI are fundamentally reshaping offensive cyber operations, and the expertise to harness these capabilities increasingly resides outside government, in AI-native companies. If the U.S. and its allies want to remain competitive in offensive cyber operations, they will need to explore how to use commercial technologies as force multipliers. Over the past few years several startups have emerged to bring commercial AI technology to U.S. and allied governments to accelerate their offensive cyber operations, and we are just at the beginning of this shift in the market.

The Role of OCO in National Security

While public acknowledgment is new, OCO has played an important part of national security for decades. The U.S. Department of War (DoW) has been involved in cyber operations since the 1990s, with offensive capabilities gaining major prominence in global conflicts beginning in the mid-2000s through landmark nation-state incidents including Russia-linked DDoS attacks on Estonia in 2007, cyber operations surrounding the 2008 Russo-Georgian war, and the 2009 Stuxnet attack that caused the first known cyber-induced physical damage to Iranian nuclear facilities.

It was the discovery of two major Chinese cyber campaigns, Volt Typhoon and Salt Typhoon, in 2023 and 2024 that really sounded the alarm. By exposing Chinese cyber campaigns designed to compromise American critical infrastructure and infiltrate U.S. telecommunications systems, these operations proved that the homeland is now directly at risk from cyber attacks. As our country comes to rely increasingly on digital systems to control everything from nuclear power plants to autonomous taxis and satellites, offensive cyber operations will only become more significant in future conflicts.

The U.S. has responded to this shifting landscape by moving OCO to the forefront beginning with the 2010 creation of CYBERCOM and its subsequent elevation to a full Unified Combatant Command in 2018. In addition to the campaigns in Iran and Venezuela, CYBERCOM has also publicly acknowledged several other successful operations. In 2016, CYBERCOM conducted Operation GLOWING SYMPHONY, which dismantled ISIS’s global propaganda and recruitment infrastructure by infiltrating their servers, deleting massive amounts of data, and locking operatives out of their own media networks. In 2018, they conducted a campaign against the Internet Research Agency (IRA), the Russian troll farm that ran an influence operation targeting Americans before the 2016 presidential elections, shutting down the IRA’s internet access to protect the 2018 midterm elections.

To further support these missions, the government is putting significant capital behind the effort, most notably through the “One Big Beautiful Bill” (OBBB), which allocates $1B for offensive cyber operations in INDOPACOM through FY29 and another $250M for the expansion of CYBERCOM’s “artificial intelligence lines of effort.” Further, CYBERCOM has requested another $473.4M in its FY26 budget for Cyber Operations Technology Support which includes line items for AI, data and sensors, data analytics, cyber weapons, and more (the FY26 appropriations bill has not yet passed).

China’s Cyber Power

China is one of the United States’ most capable and active adversaries in the use of offensive cyber operations. However, this wasn’t always the case – only five years ago, in 2021, experts estimated that China was a decade behind the U.S. in cyber capability. Since then, China has significantly improved their internal cyber forces and passed laws to provide offensive advantages to the CCP.

China has focused on developing the next generation of cyber talent through university programs and state-sponsored events like CTF3, live hacking, and bug bounty programs that offer a pipeline into government work. Today, China is thought to have a cadre of cyber operators 50x the size of the U.S. They have also enforced policies enacted in the 2017 Cybersecurity Law that require the private sector to collaborate with the government to augment their offensive cyber capabilities by sharing newly discovered vulnerabilities with them before they are shared externally. The private sector helps in other ways too, both by offering hacking services on behalf of the government and by providing tools and training, such as cyber ranges that allow operators to practice attack techniques and learn how to bypass defensive measures, serving as rich training environments to learn on.

For example, major Chinese technology firms such as Huawei, Qihoo360, QiAnXin, and NSFocus provide services directly to the Chinese military – Qihoo360, China’s leading antivirus company, even directly assisted with a Chinese hack of Anthem, an American health insurance provider. The PLA has embedded units within commercial Chinese cybersecurity firms. Unlike the U.S., both China and Russia allow non-government entities, including commercial companies, to conduct their own cyber attacks, as long as they do not infringe on government priorities. The U.S. is considering proposals to do the same. At the very least, the U.S. government should leverage capabilities developed in the commercial sector as force multipliers.

Looking ahead, any future conflict with China is unlikely to resemble the counterinsurgency or counterterrorism campaigns of the Global War on Terror, where U.S. forces faced technologically unsophisticated adversaries and enjoyed overwhelming dominance on the ground. A future conflict with China is far more likely to be maritime, air, space, and cyber-centric rather than a large-scale land war, with cyber operations playing a central role in shaping escalation, degrading command and control, and constraining U.S. freedom of maneuver before kinetic forces are employed. Critically, cyber operations often occur below the traditional threshold of armed conflict, allowing states to operate at scale with lower perceived risk of escalation – which China has repeatedly demonstrated its willingness to do through sustained campaigns (like pre-positioning cyber attacks in U.S. critical infrastructure such as water treatment plants and power grids) that would be far more escalatory if conducted through conventional military means.4

Authorities and the Private Sector Role

Understanding where these operations live within the government requires a look at legal authorities. Most operations fall under either Title 10 (Armed Forces / military disruption) or Title 50 (Intelligence Community / espionage) of the U.S. Code. While these authorities remain strictly within the government, the private sector has always played a role as a supporting partner.

Until recently, there were essentially no VC-backed private companies operating in the offensive cyber space. Private companies operating in the offensive cyber market generally fall into three core business models: (1) services providers, including defense primes and specialized boutique firms; (2) vulnerability research firms and zero-day marketplaces, which discover and sell previously unknown vulnerabilities and exploits; and (3) turnkey offensive platforms, offered by international vendors that provide “access-as-a-service” capabilities. Groups (2) and (3) frequently operate in legal gray zones.

The Services Model: Defense Primes

Historically, large defense primes like RTX (Raytheon) and its spinoff Nightwing, L3Harris, ManTech, Lockheed, and Peraton have leveraged a services approach to provide “Full-Spectrum Cyberspace Operations” to the U.S. government. This includes vulnerability research, exploit development, electronic warfare (EW), and managed infrastructure like “firing platforms,” as well as general support for computer network operations. Smaller boutique contractors, often founded and staffed by former government employees, frequently subcontract with these large primes for supporting work.

These large defense primes and smaller contractors typically have “butts in seats” engineering services business models, in which contractors work directly for the U.S. government, selling human labor hours rather than products. Organizations like NSA, CIA, FBI, and CYBERCOM hire these contractors to help craft cyber kill chains by finding vulnerabilities and building exploits based on those vulnerabilities. However, today, only U.S. government employees are allowed to actually “pull the trigger” to use those exploits.

Selling Exploits

Beyond service-based contracting, specialized vulnerability research firms and marketplaces find, collect, and sell exploits to intelligence agencies and other hacker groups as discrete products rather than labor hours. Vulnerability research firms are generally small, boutique teams of full-time experts (often former government intelligence officials) focused on discovering vulnerabilities, building exploits, and selling them directly to intelligence agencies or other hacking groups. Notably, a significant number of zero-day vulnerabilities used in cyber attacks come from these commercial vulnerability vendors – a Google study found that in 2023 and 2024, around 45% of vulnerabilities that were exploited “in-the-wild” were attributed to commercial vendors that sell capabilities to government customers.

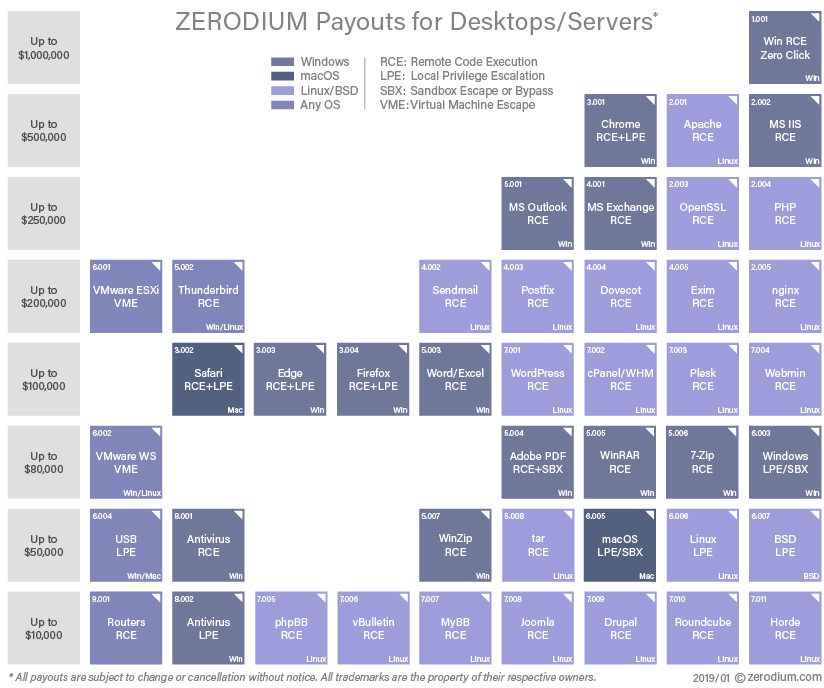

Often, rather than selling exploits directly to intelligence agencies or hacking groups, vulnerability researchers will sell their vulnerabilities and exploits to “zero day” marketplaces such as Crowdfense, Operation Zero, and Zerodium (which has since gone out of business). These firms act as middlemen, buying vulnerabilities and exploits from vulnerability researchers and then selling them to governments or other hacker groups. Zero day marketplaces set prices for different vulnerability classes – vulnerabilities in mobile devices, particularly iPhones, tend to be the most valuable given iPhone’s tight security and valuable information, whereas a vulnerability for something like an IoT camera may be less valuable, as cheap IoT devices tend to be relatively easy to penetrate and provide lower value information.5

Many of these firms operate in legal and moral gray zones, selling vulnerabilities to the highest bidder which may be an American or allied intelligence agency, a cyber crime organization, or another foreign government.

Turnkey Solutions: Access-as-a-Service

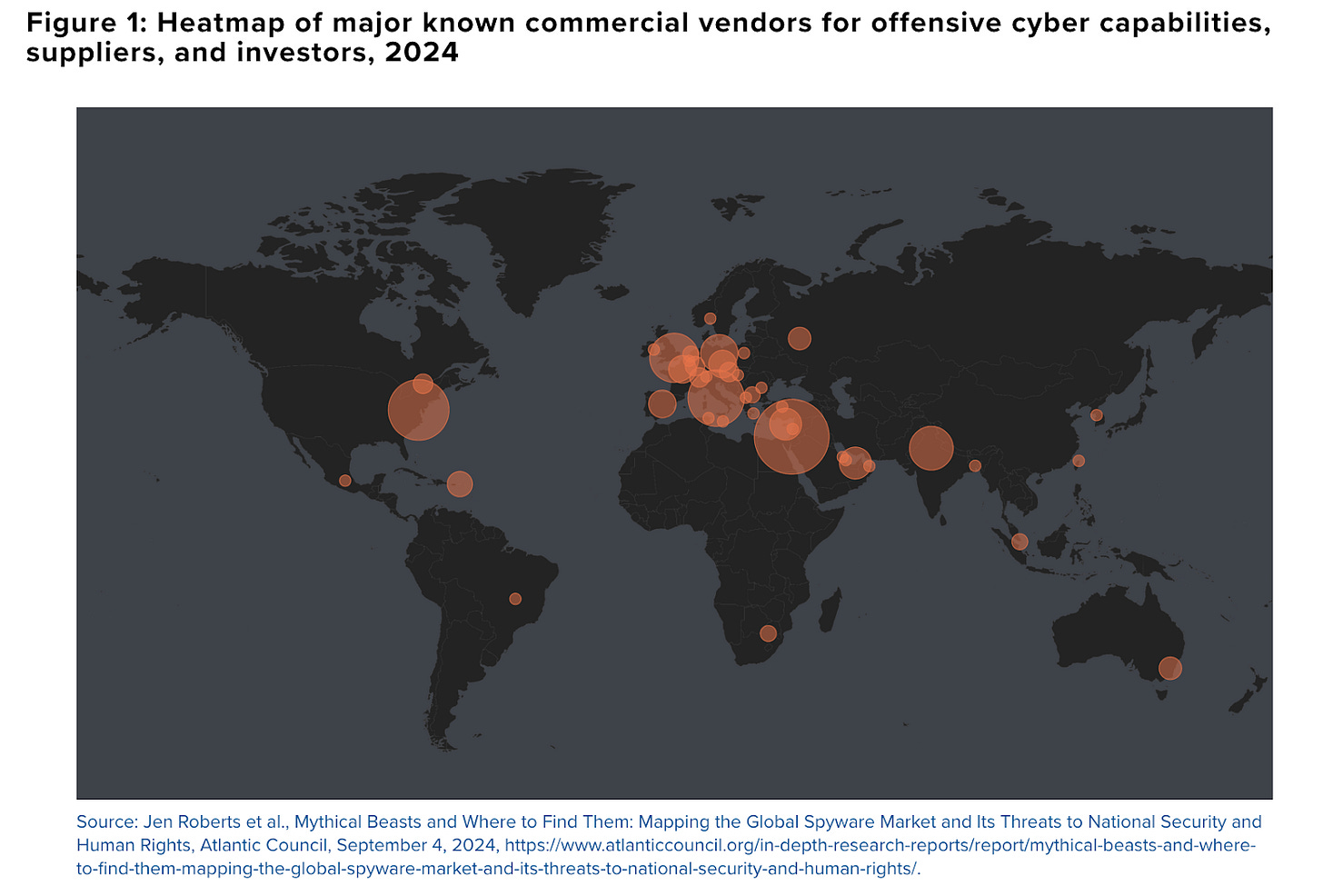

Finally, perhaps the most controversial players in the offensive security market are the “access-as-a-service” firms like NSO Group, Memento Labs (fka HackingTeam), Candiru, Paragon (an Israeli firm recently purchased by a U.S. private equity firm for $500M), and Intellexa. These firms are almost all based internationally, as it is illegal for American companies to sell “access-as-a-service” products outside of the U.S. Unlike vulnerability research firms, which sell operators information about software flaws that can be developed into exploits, “access-as-a-service” providers bundle exploits with proprietary tooling and sell ready-made access to target systems without ever disclosing the underlying vulnerabilities. For example, rather than selling a vulnerability for an IoT camera, an access-as-a-service provider would just provide a video feed from a vulnerable camera that they’ve already compromised.

Historically, U.S. intelligence agencies have not purchased tools from access-as-a-service providers. The U.S. IC reportedly prefers to find or purchase vulnerabilities and build and execute their own exploits based on those vulnerabilities. However, many foreign governments that lack the capital and talent to develop their own offensive cyber organizations will work with access-as-a-service providers in order to gain access to high end offensive cyber capabilities without investing significant human or financial resources to gain those capabilities. Note that many access-as-a-service vendors, including Israeli firms such as Candiru and NSO Group, have struggled operationally and commercially since being placed on the U.S. government’s Entity List.

The AI Force Multiplier

The emergence of AI is fundamentally changing the OCO game by providing unprecedented speed and scale to operations. AI models’ cyber capabilities are currently doubling every six to eight months, allowing for the rapid identification of vulnerabilities and the creation of exploits that used to take months of manual labor. AI is now capable of finding net-new vulnerabilities, scanning networks for vulnerable entry points, and using code-generation agents to build executable exploits on the fly. It also dramatically scales the use of “n-day” vulnerabilities, allowing attackers to check millions of systems for known flaws in the time it would take a human to check one. While human operators are limited by biological reaction times, AI can orchestrate hundreds of tactical operations per second, pushing us into an era of “machine-speed cyber warfare.”

Furthermore, AI allows less-skilled operators to perform high-level tasks, for example orchestrating everything from simple social engineering and deepfake phishing to complicated, multi-stage data exfiltration operations. This acts as a massive force multiplier for a workforce that has long suffered from a talent shortage, but it also means our adversaries, who are becoming increasingly aggressive in the cyber domain, can scale their hostility with fewer resources.

Crucially, while government agencies like NSA and CIA have started experimenting with using AI for relevant workflows, ultimately most of this innovation in AI is being developed in the private sector rather than within government. While there are safety guardrails for private, frontier models like Anthropic’s Claude, open-source models, such as DeepSeek, Llama 3, or Mistral, can be run on local machines with no central oversight or kill switch. If our government fails to rapidly adopt AI-driven capabilities, it risks being outpaced and left strategically vulnerable in the accelerating global arms race of cyber warfare. This creates a massive opening for VC-backed, product-based companies to build software that is faster to deploy and easier to scale than bespoke internal tools or human operators.

The Emerging Market for Offensive Cyber Startups

In this emerging market, new startups are looking to leverage AI for a whole host of tasks necessary for OCO including vulnerability research and binary reverse engineering, initial access and attack surface mapping, generating and executing exploit code, and cyber threat intelligence collection. Where previous generations of tools flagged potential weaknesses and left the exploitation to human experts, today’s startups deploy autonomous agents capable of “thinking” like an adversary – dynamically navigating complex codebases, reversing binaries in seconds, and orchestrating multi-step exploits without human intervention. By fusing high-fidelity threat intelligence with agentic autonomous operations, this market has turned sophisticated offensive capabilities into a scalable enterprise product.

Vulnerability Research

Generative AI has fundamentally changed vulnerability research and exploitation. One of the primary commercial use cases for LLMs is code generation – this same technology can also be used to find vulnerabilities in code. Agents can also find vulnerabilities in web and desktop applications without source code access by using computer use agents6 to interact with those applications in order to find vulnerabilities (ex: SQL injections, cross-site scripting attacks, etc).

For example, companies like Autonomous Cyber7 deploy computer use agents to navigate applications and code-understanding agents to analyze codebases, enabling automated discovery of security vulnerabilities. Autonomous Cyber has already used AI to autonomously discover several net new CVEs. Similarly, according to Anthropic, Chinese state sponsored hackers successfully used browser use agents to discover a SSRF vulnerability in target web applications. Several startups including RevEng.AI and Delphos Labs have also emerged using LLMs for binary reverse engineering (the process of analyzing compiled binary code), enabling offensive cyber analysts to quickly understand third party code in order to begin the exploitation process.

Initial Access and Attack Surface Mapping

Companies like Twenty replace traditional, labor-intensive manual probing with autonomous, agent-led orchestration. Their platforms deploys AI agents that operate across the reconnaissance and exploitation phases, autonomously gathering and fusing disparate data streams into a unified, interconnected digital twin of a target's infrastructure. This gives operators an interconnected map of resources, configurations, and exposures which serve as the basis for operators to conduct autonomous attacks with extreme precision and trust. In the context of government OCO, this type of tooling acts as a force multiplier, allowing operators to conduct more cyber operations faster and with fewer resources, providing a scale and speed advantage. Method Security takes a similar approach.

Generating and Executing Exploit Code

Not only can these new startups find net new zero-day vulnerabilities and map out initial network access points, they can also use AI agents to generate and execute exploits that take advantage of those vulnerabilities. Companies like Autonomous Cyber use code generation agents to autonomously generate exploit code based on known vulnerability chains. Similarly, Dreadnode provides an AI-driven offensive security platform that combines advanced red-teaming tools, autonomous offensive agents, and comprehensive evaluation frameworks to help security teams build, deploy, test, and measure AI-powered attack capabilities and assess vulnerabilities in systems and models at scale. Agents can also help organizations scale the exploitation of n-day vulnerabilities by autonomously scanning targets to find and exploit known vulnerabilities. Tool calling agents can use existing offensive security tools and post-exploitation toolkits, the same way a human operator would, to take advantage of known vulnerabilities.

Cyber Threat Intelligence

In addition to finding and exploiting vulnerabilities in target systems, a number of commercial companies have emerged to push forward the state of the art of cyber threat intelligence (CTI). In order to actually exploit a target, analysts need to understand their targets. One source of information about target systems is CTI, which can help analysts understand how target networks are architected, where vulnerabilities may lie, known tactics, techniques, and procedures, which detection and protection tools targets have in place, and may even provide analysts with target credentials that may have leaked on the dark web.

Today, CTI incumbents are excellent at collecting relevant information on emerging cyber and fraud threats from the dark web, deep web, and other sources. However, analysts still need to wade through troves of data to extract meaningful insights. Startups like Overwatch Data, BeeSafe AI, and Specters AI have emerged to build AI-native CTI tools that leverage advances in AI agent technology. AI agents can improve both the collection and analysis of CTI. For example, AI agents could be used to automate the operation of “sockpuppet” social media accounts, that ingest a site’s context, learn from other users’ behavior, and interact with the platform the way a real human user would in order to extract information that could help offensive cyber operators.

Once data is collected, AI agents can help extract and summarize insights by querying multiple data streams to enrich information to present analysts a more complete picture of targets. AI agents can automatically generate CTI reports and can even suggest actions analysts could take or vulnerabilities to exploit based on the information collected. In the future, agents could even automatically generate exploits based on data collected from CTI.

Commercial Penetration Testing Platforms

In addition to advancing the state of offensive cyber, advances in AI also unlock a stronger cyber defense. With AI, organizations can move beyond periodic security audits and unpatched vulnerabilities toward continuous, AI-led red teaming, providing a defensive posture that finally keeps pace with the increasingly sophisticated, AI-augmented threat actors appearing in the wild.

There are a number of companies like RunSybil, XBOW, Tenzai, and Staris AI taking these same OCO technologies and applying them to the commercial penetration testing space in order to help organizations identify and patch vulnerabilities on their own networks. While these companies are not focused on offensive use cases today, in the future they could look at deploying their software for offensive government uses.

Advice for Startups

Founders entering the offensive cyber market must approach company-building with a fundamentally different playbook, shaped by government procurement dynamics, operational trust requirements, and extended timelines to scale. Successful companies in this space will:

Understand Government Needs: Follow defense blogs, track public statements from government officials, attend relevant conferences, and spend time speaking with end users to deeply understand their operational needs. Agencies and groups with current authorities and budget for OCO include CYBERCOM (including CNMF, ARCYBER (Army), FLTCYBER (Navy/10th Fleet), AFCYBER, MARFORCYBER, NSA (CNO), CIA (CCI), and FBI Cyber Division.

Include Former Operators: Your team should include people who have operated under Title 10 or Title 50 authorities who deeply understand operator needs.

Plan for the Long Haul: Many USG sales cycles can take multiple years to identify stakeholders, satisfy requirements, and complete cybersecurity compliance processes. Plan for multiple years of development before achieving consistent revenue.

Build a Specialized Sales Team: You need a federal sales team that is deeply connected within the intelligence and defense communities. Don’t hire a single, generic “Federal BD Lead.” Instead, hire customer-specific sales leadership, with dedicated leaders for each USG customer who have deep, firsthand experience operating in that organization (for example, one sales lead focused on NSA, another on CIA, another on FBI, another on CYBERCOM, and so on).

Partner with the Primes: Established defense primes (RTX, ManTech) are often the best path to large contracts via subcontracting in the early days of a company.

Prioritize Security and Clearances: Build strong cybersecurity into your own company from day one and start the FCL8 and ATO9 processes early.

Define Your Ethical Lines: Be clear and transparent about where your company stands on the ethical usage of its tools, particularly when engaging with international agencies.

Explore Selling to Less Mature Agencies: Federal agencies with sophisticated cyber programs like NSA can be difficult customers to sell into, as they have already purchased or built in-house OCO tooling. However, as cyber becomes an increasingly important domain, other military and law enforcement agencies are working to stand up their own cyber capabilities, and may move more quickly to acquire new tooling that lowers the barrier to entry to conduct OCO without expert operators. Organizations like DEA as well as allied international intelligence and law enforcement agencies that have less mature cyber operations may be good target customers to pursue in parallel with more mature agencies in order to gain early revenue and user feedback.

Conclusion: The Billion-Dollar Pivot to Autonomous Offense

The convergence of aggressive government policy, billion-dollar budget allocations like the OBBB on top of the billions already spent annually, and the arrival of machine-speed AI has created a “perfect storm” for the next generation of cybersecurity founders. For decades, the offensive market was a walled garden dominated by labor-intensive service contracts and legacy defense primes. Today, that wall is coming down. The government’s call to “destigmatize” and privatize offensive capabilities has opened a massive vacuum that only product-led startups can fill.

This shift is not optional. China has demonstrated both the intent and the capacity to integrate commercial technology, AI, and state power into a unified cyber force operating at scale and often below the threshold of armed conflict. In contrast, a U.S. model that relies primarily on bespoke, internally developed tools risks falling behind an adversary that iterates faster, fields larger forces, and weaponizes commercial innovation as a matter of national strategy. Maintaining U.S. competitiveness in cyber will require embracing commercial vendors not as auxiliary support, but as core force multipliers.

The opportunity for founders is no longer just about building better scanners; it is about building the autonomous infrastructure of modern defense. By shifting from a human-centric services model to an AI-native agentic model, startups can offer the speed and scale that the public sector desperately needs but cannot build internally. In this new era of automated red-teaming and machine-speed exploitation, the advantage belongs to the agile. For those who can navigate the complexities of federal sales and ethical guardrails, the prize is a foundational role in the new national security stack. The global cyber arms race has begun, and for the first time, the most powerful weapons are being built by startups.

As always, please reach out if you or anyone you know is building at the intersection of national security and commercial technologies. And please reach out if you want to further discuss the ideas expressed in this piece or the world of NatSec + tech + startups. Please let us know your thoughts! We know this is a quickly changing space as conflicts, policies, and technologies evolve.

MCP = Model Context Protocol. MCP is a standardized interface that lets AI agents securely discover, reason over, and take action across external tools, data sources, and services

SSRF = Server-Side Request Forgery

Capture The Flag (CTF) competitions are gamified hands-on training exercises for offensive cyber.

For more on the current state of China’s offensive cyber capabilities and the role of commercial companies in China’s OCO, we highly recommend the following reports: the U.S.-China Economic and Security Review Commission’s 2022 report on China’s Cyber Capabilities; Winnona DeSombre Bernsen’s Atlantic Council report “Crash (exploit) and burn: Securing the offensive cyber supply chain to counter China in cyberspace”

For more on zero day marketplaces, we highly recommend reading Nicole Perloth’s book This is How They Tell Me the World Ends.

Computer use agents are agents that can control digital environments like browsers, terminals, file systems, and applications.

For more on Autonomous Cyber, check out this podcast interview with the founders.

FCL = Facilities Clearance

ATO = Authority to Operate

Note: The opinions and views expressed in this article are solely our own and do not reflect the views, policies, or position of our employers or any other organization or individual with which we are affiliated.